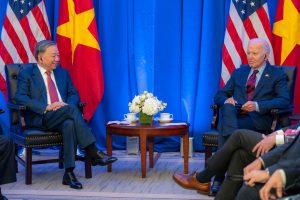

To Lam, Vietnam’s president and the general secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV), has just wrapped up his first visit to the United States, a month after his visit to China. Besides participating in the 79th session of the United Nations General Assembly, Lam met U.S. President Joe Biden to celebrate the anniversary of the U.S.-Vietnam Comprehensive Strategic Partnership (CSP) and the upcoming 30th anniversary of the normalization of U.S.-Vietnam diplomatic ties. The Biden administration probably made a last-minute schedule adjustment in order for Biden to meet Lam, since the Vietnamese official press release before the visit did not mention the bilateral meeting. The schedule change further confirmed Vietnam’s growing importance in U.S. Indo-Pacific policy.

Lam’s visit came two weeks after Vietnam’s Defense Minister Phan Van Giang’s meeting with his U.S. counterpart Lloyd Austin at the Pentagon, amid speculation that Hanoi is looking to buy Lockheed Martin C-130 cargo planes. Giang was a member of Lam’s delegation to New York City as well. In September 2023, there were reports of Vietnamese and U.S. officials discussing the sales of F-16 fighter jets, but so far the deals have not materialized. While external security cooperation has shown little progress, internal security cooperation is improving apace. Minister of Public Security Luong Tam Quang and Deputy National Security Advisor for Cyber and Emerging Technologies Anne Neuberger pledged closer cooperation against cybercrimes. Vietnam is the third most hacked country in Southeast Asia, and the government has designed cybercrimes as a threat to national security. Vietnam will tremendously benefit from a more resilient cyber network and cutting edge U.S. technologies as it carries on with the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Closer U.S.-Vietnam internal security cooperation is a logical move to push the bilateral ties forward in the face of China’s pressure to keep Vietnam neutral.

However, what stood out from the summit was not the now often-repeated diplomatic statements of friendship and reconciliation, but Vietnam’s interpretation of the history of U.S.-Vietnam relations. Next year will mark the 50th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War, so how Vietnam handles the anniversary tells us much about its perception of the U.S. as a partner. Lam gave the United States a glimpse of that in his address at the Asia Society in New York City, when he remarked that “during the August Revolution, our American friends were the only foreign force next to President Ho Chi Minh and were invited to attend the Declaration of Independence Ceremony on September 2, 1945.” He mentioned President Ho Chi Minh’s many attempts to reach out to the Harry S. Truman administration to establish cooperation, but “due to historical conditions and contexts,” Vietnam and the U.S. were at war for 20 years followed by 20 years of frozen relations.

Lam’s remark fit the 16-word guideline of the U.S.-Vietnam CSP that the late General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong laid out last year, that the U.S. and Vietnam should put aside the past. The remark also echoed Trong’s emphasis on the anti-Japanese U.S.-Vietnam alliance during World War II. Importantly, by stressing the role the U.S. played in the independence of Vietnam, and Truman’s missed opportunity afterwards, Lam wanted his host to remember that the U.S. can develop fruitful relations with a communist government so long as it does not threaten the political survival of such a government.

Lam’s comment on the history of U.S.-Vietnam relations is not an isolated phenomenon but fits a preexisting general pattern of Vietnam’s efforts to strike a balance among the major powers through its interpretations of history with said powers, most importantly China. Vietnam has de-emphasized past conflicts with the major powers in order to convey its friendly intentions towards all of them per its post-Cold War omnidirectional foreign policy.

Last month when visiting China, Lam showed Vietnam’s appreciation for China’s help during its wars of independence against France and unification against the United States by visiting the Memorial House of Chairman Mao Zedong and “red addresses” related to the Vietnamese communist movement in Guangzhou. During the 70th anniversary of the Dien Bien Phu Victory in May, Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh also thanked China and the former Soviet states for their precious help during the First Indochina War, a significant admission considering Hanoi’s rhetoric of self-reliance. It is worth noting that during the acrimonious years of Vietnam-China relations in the late 1970s, Hanoi often accused China of dividing Vietnam at the 17th parallel at the Geneva Conference and of conspiring to control Vietnam via Chinese military aid during the Vietnam War. As Vietnam looked to normalize ties with China in the late 1980s, it again emphasized Chinese assistance during the two conflicts and has done so since.

Vietnam has recently allowed for the commemoration of the 1979 Vietnam-China border war, but its main message is to cherish contemporary Vietnam-China relations by learning from history and avoiding stoking past hatred. 2025 will also mark the 75th anniversary of the establishment of Vietnam-China diplomatic ties, an anniversary that Vietnam considers important to the historical understanding of modern Vietnam-China ties. Vietnam putting aside the past with China is no different in terms of logic from it putting aside the past with the United States.

With respect to Russia, the only major power that Vietnam was rarely on bad terms with, Vietnam often expresses its appreciation for the former Soviet Union’s help during its “two wars” of independence and unification. To avoid upsetting China, Vietnam does not mention the critical Soviet support during the Vietnam-China border war and the decade-long standoff in the 1980s, contrary to its frequent mention of such support in the 1980s. Such a move is in line with the Russian government’s efforts to reconcile with China in the 1990s and thus did not make Russia upset. Importantly, Vietnam balanced its ties between Russia and Ukraine by appealing to Ukraine’s Soviet past, noting that “Vietnam fondly remembers the support from the Soviet people, including Ukrainians, during its national liberation and reunification” efforts. This is to negate any accusations that Hanoi is not supporting Kyiv due to the historical debts to Moscow, as Hanoi technically also had historical debts to Kyiv.

Vietnam’s conscious efforts to balance its ties among the great powers via its official interpretation of history were made clear shortly after Lam’s departure from the United States. BBC Vietnamese reported that his remark about the United States being the “only foreign force next to President Ho Chi Minh” was deleted from Tuoi Tre Online’s transcript of the speech. Vietnam made the change after the fact because the remark downplayed the massive support that the Soviet bloc and the Chinese Communist Party gave to the Indochinese Communist Party and Ho during his time in China, which allowed the Vietnamese communists to later establish the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in 1945. Hanoi did not want to create the false impression that it was leaning on the U.S. side by downplaying Chinese communist assistance to an extreme extent. The elimination of the remark conformed to Hanoi’s neutral foreign policy and did not signal any hostile intentions towards the United States.

History is not simply about the past but about how the present shapes the past to serve a political purpose. For Vietnam, (re)interpreting history is to signal a peaceful intention towards the major powers to best advance its national interests as global polarization intensifies. Hanoi is telling different versions of history depending on what its major diplomatic partners want to hear. And of course, behind all the attempts at historical (re)interpretation, the single unchanged history lesson that informs Vietnam’s omnidirectional foreign policy is to avoid becoming a battleground of the major powers once again.