The Japanese Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) presidential election concluded on September 27 with the highest number of candidates in the party’s history. It was a closely contested race, and while Takaichi Sanae nearly made history by becoming Japan’s first female prime minister, it was the veteran politician Ishiba Shigeru who ultimately emerged victorious, securing crucial votes from the Kishida faction.

Ishiba is no stranger to Japanese politics. His career was inspired by his family’s friend, former Prime Minister Tanaka Kakuei, who was instrumental in establishing China-Japan diplomatic relations.

However, Japan now faces heightened tensions with China. The tragic murder of a 10-year-old Japanese child on his way to school in southern China has sent shockwaves through the country, prompting companies like Panasonic to allow their China-based staff to relocate to Taiwan. Additionally, in late August a Chinese reconnaissance aircraft breached Japan’s territorial airspace for the first time.

Shortly before the LDP election, a Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force (SDF) destroyer sailed through the Taiwan Strait alongside Australian and New Zealand naval forces, highlighting the complex geopolitical landscape.

A former defense minister, Ishiba is well known as a defense policy wonk. His victory will have important implications for the future of Japan-Taiwan relations.

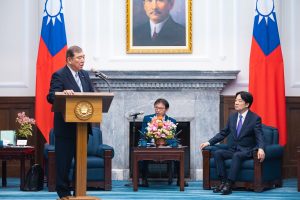

In August, just a month before the election, Ishiba visited Taiwan and met with President Lai Ching-te. During his Taiwan visit, Ishiba reaffirmed his intention to run for LDP president and stressed that “today’s Ukraine might become tomorrow’s East Asia.” He emphasized the importance of developing “integrated deterrence” through Japan-Taiwan cooperation, though he notably avoided repeating former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo’s statement that “a Taiwan contingency is a Japan contingency.”

Instead, Ishiba highlighted his vision for creating a NATO-like framework for Asia. In a televised discussion on Fuji Television with the other LDP candidates, he proposed that the defense treaties between Japan and the United States, as well as between the U.S. and the Philippines, could evolve from bilateral agreements into a collective security arrangement similar to the Australia, New Zealand, United States (ANZUS) Security Treaty.

On the same show, when asked whether a Taiwan contingency would be categorized as an “important influence situation” or a “survival-threatening situation,” Ishiba suggested it would, at the very least, fall under the former category. The distinction is significant: In an “important influence situation,” the Japanese Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) could only provide rear logistical support to U.S. forces, while a “survival-threatening situation” would permit the JSDF to exercise collective self-defense.

Ishiba also raised a critical issue: If the United States were to request Japan to allow Taiwan’s air force to use the Kadena Air Base in Okinawa, Japan’s refusal could end the Japan-U.S. security alliance. Under the current framework, any use of U.S. bases by forces other than U.S. troops requires prior consultation with the Japanese government, as stipulated in Article 3 of the security treaty. Such a decision would place Japan in a difficult position vis-à-vis China, as it would effectively align Japan with the U.S. and Taiwan, potentially making Japan a target of Chinese retaliation.

Despite these complexities, Ishiba’s comments suggest that his concept of “integrated deterrence” remains rooted in the Japan-U.S. alliance. However, at the same time he has also called for a more equal partnership, labeling the current arrangement as “asymmetrical.” Achieving this balance could prove challenging if Donald Trump returns to power in the United States, given his previous rhetoric about alliances being a “burden” and his insistence that Japan should shoulder more responsibility and cover more of the expenses incurred at the U.S. forces stationed in Japan.

In conclusion, while Taiwan may face challenges in achieving significant diplomatic breakthroughs with Japan under Ishiba’s leadership, given his focus on integrated deterrence, there is a path forward. For Taiwan to improve its relationship with Japan, it is not solely about engaging directly with Tokyo. Taiwan must also enhance its visibility and role within the Japan-U.S. alliance by strengthening its cooperation with the United States. By positioning itself as a more integral and visible actor in the broader Japan-U.S. strategic framework, Taiwan can indirectly foster deeper ties with Japan.