Lee Hsien Yang, the youngest son of Singapore’s founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, announced yesterday that he has been granted political asylum in the United Kingdom, on the grounds that he faces “a well-founded risk of persecution” in Singapore.

The three children of Lee Kuan Yew have been estranged since 2017, when Lee Hsien Yang, 67, and his late sister Lee Wei Ling publicized a conflict with their older brother, former Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong. The dispute centered on whether to demolish the family home in line with their late father’s wishes.

In a statement posted to his Facebook account yesterday, Lee Hsien Yang said that he and his sister had “feared the abuse of the organs of the Singapore state against us” in connection with the feud.

“They prosecuted my son, brought disciplinary proceedings against my wife, and launched a bogus police investigation that has dragged on for years,” he wrote in the post. “On the basis of these facts, the U.K. has determined that I face a well-founded risk of persecution, and cannot return safely to Singapore.”

According to a Bloomberg report, which cited a letter from the U.K. Home Office shared by Lee Hsien Yang, the government approved the younger Lee’s asylum request in August, allowing him to remain in the country for five years.

Lee Hsien Yang, the former CEO of Singapore Telecommunications, has lived in self-imposed exile since June 2022, when he and his wife Lee Suet Fern were called in for police questioning into allegations that they gave false evidence in judicial proceedings regarding their father’s will. In his Facebook post, Lee said that he applied for asylum in the U.K. that same year.

Lee Hsien Yang’s announcement is the latest development in a Shakespearean family feud over the fate of the family home at 38 Oxley Road. The dispute centers on the elder Lee’s wishes for the colonial-era bungalow, which was his home from the end of World War II until his death in 2015. Uncomfortable with the family’s living quarters being thrown open to the public, Lee Sr. said in his final will that he wanted it demolished once his daughter no longer lived there. While Lee Hsien Yang and Lee Wei Ling have pushed to have the home demolished, the Singaporean government set up a ministerial committee that has raised the possibility of preserving the house in some manner.

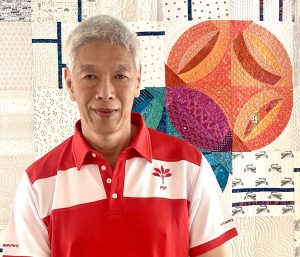

In 2017, Lee Hsien Yang and Lee Wei Ling went public with claims that they felt threatened in trying to fulfil their late father’s wish to demolish the house. They also accused Lee Hsien Loong of abusing his influence in government in order to preserve the home and advance his personal dynastic agenda. The younger Lee later joined the opposition Progress Singapore Party.

The dispute over 38 Oxley Road was inflamed earlier this month after the death of Lee Wei Ling, who lived her final years in the home. Shortly after the funeral, which Lee Hsien Yang did not attend, he announced that he had applied for permission to demolish the house and build a small private residence on the site in order to “honor my parents’ last wishes.”

In an interview with The Guardian, which was published yesterday, in line with the announcement of his successful asylum claim, Lee Hsien Yang burned what few bridges remain, launching a stinging attack on Singapore’s squeaky-clean international image.

“Despite the very advanced economic prosperity that Singapore has, there’s a dark side to it, that the government is repressive,” he told the British newspaper. “What people think, that this is some kind of paradise – it isn’t.” He also accused Singapore of acting as a “key facilitator for arms trades, for dirty money, for drug monies, crypto money.”

“People need to look beyond Singapore’s bold, false assertions and see what the reality really is like,” he added. “There is a need for the world to look more closely.”

In statements sent to the press, the Singaporean government said there is “no basis” to Lee Hsien Yang’s allegations that he had been subject to “a campaign of persecution.” It also rebutted his claims that the country was repressive.

“Singapore’s judiciary is impartial and makes decisions independently. This is why Singaporeans have a high level of trust in the judiciary,” it said. It noted that there are no legal restraints on Lee and his wife returning to Singapore. “They are and have always been free to return to Singapore,” it added.

Despite these rebuttals, it is hard to state how embarrassing the current situation is for the People’s Action Party (PAP). To hear a son of the revered Lee Kuan Yew endorse the sorts of criticisms that are generally only heard from political exiles, rogue academics, and critical foreign researchers, and have been successfully anathematized inside Singapore itself, certainly complicates the PAP’s official narrative of dynamism, meritocracy, and frictionless efficiency.

The Singaporean government has long sought to discredit and isolate Lee Hsien Yang, and cast him as an aberration and outlier in a nation where the PAP does enjoy high levels of public support. It is likely that it will continue to do so.

However, it is much harder to avoid the fact that the U.K., a nation with close relations to Singapore where politicians have often spoken of Lee Kuan Yew’s city-state as a model, believes the younger Lee’s claims that he and his wife have been the subjects of politically-motivated persecution.

Whether or not Lee Hsien Yang’s criticisms make much difference to public opinion inside Singapore, the longer-term outlook for the PAP is cloudier than it has been for many years. As Michael D. Barr of Flinders University in Adelaide argued back in 2019, the feud within the Lee family has “tarnished and fractured” its brand and image, undermining one of the “constants” that has supported Singapore’s successes since independence in 1965. Coupled with other political trends, including growing disaffection among the Singaporean elite, he wrote, “there can be little doubt that the government faces major challenges in the medium term.”