Much ado has been made about Malaysia’s relationship with China, and nowhere is this more apparent than in trade. By now, it should be self-evident that Malaysia and China have strong economic ties: in 2023, bilateral trade reached $99 billion while Malaysia’s stock of Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) was almost $8 billion. Both governments aim to deepen this relationship further, recently emphasizing digital and green development.

In response, some observers, both in Malaysia and abroad, have raised alarm, framing Malaysia’s relationship with China as one of “overreliance” or as reflecting a “tilt” toward Beijing. Others go further, concluding that Malaysia is now unabashedly “pro-China.” However, an evaluation of bilateral and multilateral economic patterns, grounded in data rather than rhetoric, paints a more nuanced picture.

Gravity Matters

China has been Malaysia’s largest trading partner since 2009, a fact that is often cited in support of claims of economic overdependence. During his March 2023 visit to Beijing, Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim addressed this dynamic, remarking, “Given the priority, we come to China first. But as a trading nation, we must maintain excellent relationship[s] with all, including the United States.”

In its essence, Anwar’s comment, despite inadvertently creating room for sensationalist misinterpretation, alludes to the gravity model of trade, an empirically backed observation that trade flows decrease with geographical distance, all else being equal. In other words, it should not be surprising that China is such an important trading partner for Malaysia, given its size and proximity to the country, before even considering the economic structures and comparative advantages of both nations.

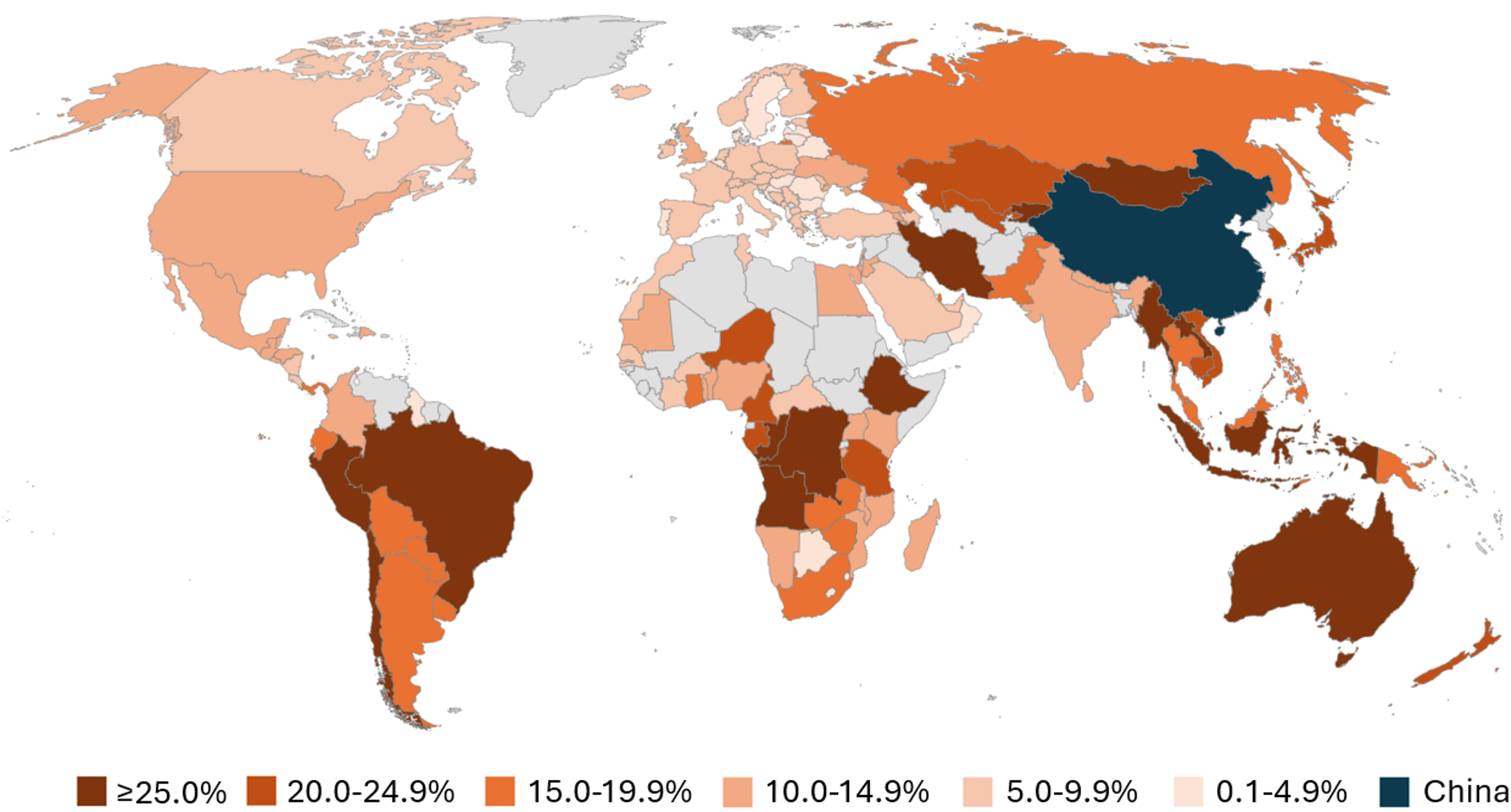

The Malaysian case is not exceptional; indeed, it mirrors global trends. According to data extracted from the U.N. Comtrade database, mainland China is the largest trading partner of 55 countries worldwide, more than any other individual nation. This includes much of the Asia-Pacific as well as Brazil, Egypt, Germany, and large swathes of sub-Saharan Africa. Across Asia, the main exceptions are small countries closer to a larger neighboring partner’s economic sphere of influence, including Nepal with India, Timor-Leste with Indonesia, and Laos with Thailand.

Therefore, the notion of “coming to China first” simply reflects global trade realities. For Malaysia, the nearby Chinese market, with its economic and population size, is an essential source of consumer demand and intermediate goods. What matters is not avoiding close ties with China but building resilience through diverse trade linkages across sectors, a goal Malaysia has demonstrably achieved, as outlined below.

It’s All Relative

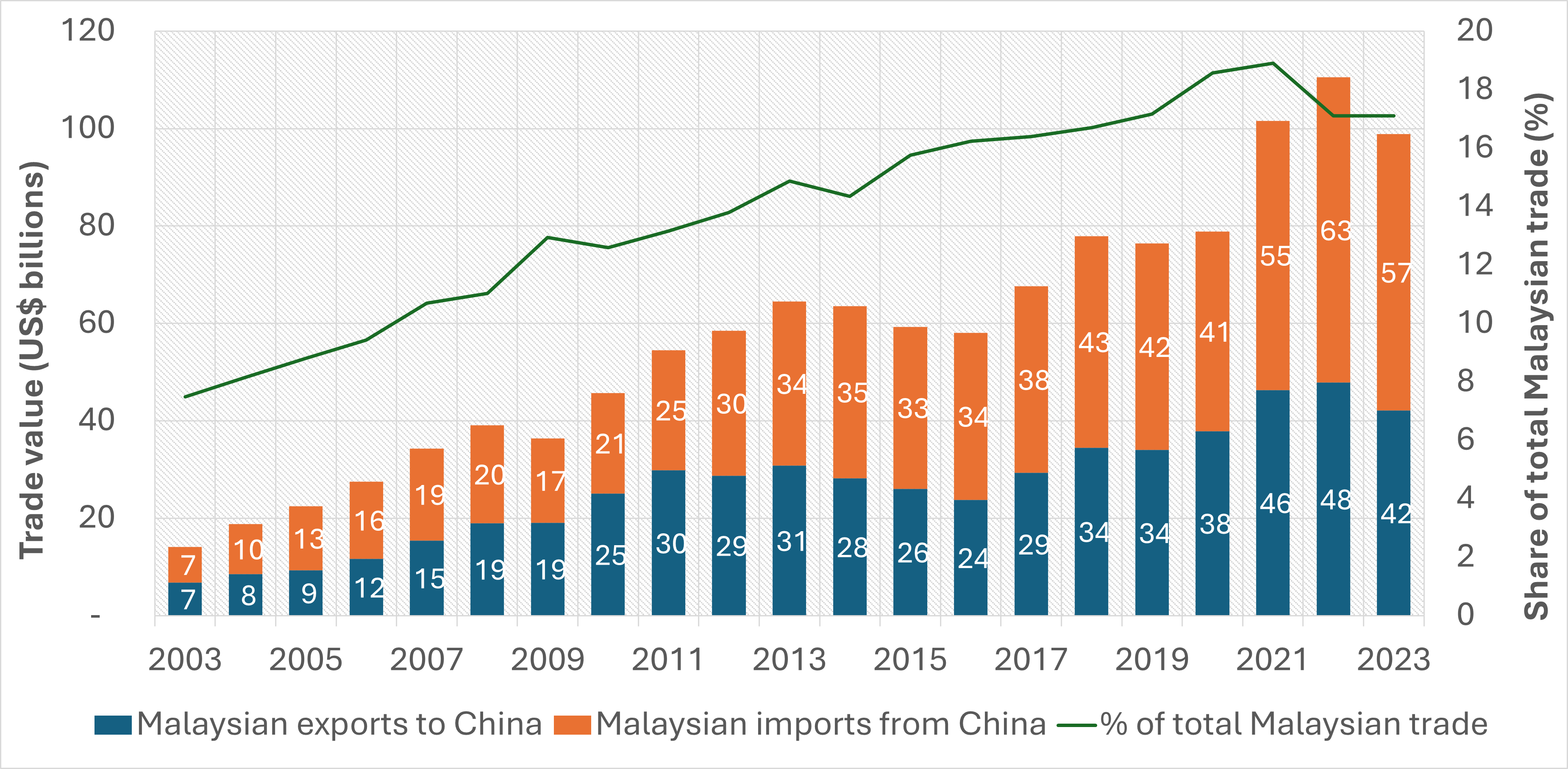

Another observation is that China’s relative importance to Malaysian trade has in fact declined in recent years. The share of Malaysia-China exports and imports to total Malaysian trade has decreased from its peak of 19 percent in 2021 to 17 percent in 2023, roughly on par with pre-pandemic trends (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Malaysia-China bilateral trade ($ billions, left) and share of total Malaysian trade (%, right). Source: Author’s calculations based on U.N. Comtrade (2024)

This trade share began to decline in 2022, the same year that bilateral trade peaked at nearly $111 billion. Since 2021, Malaysia’s overall trade growth has outpaced its trade with China, marked by a rise in ASEAN’s share of Malaysian trade from 26 percent to 27 percent. Together, these trends highlight Malaysia’s resilience amid reports of a Chinese economic slowdown, as slower trade with China has not had a direct, proportional impact on Malaysian trade outcomes.

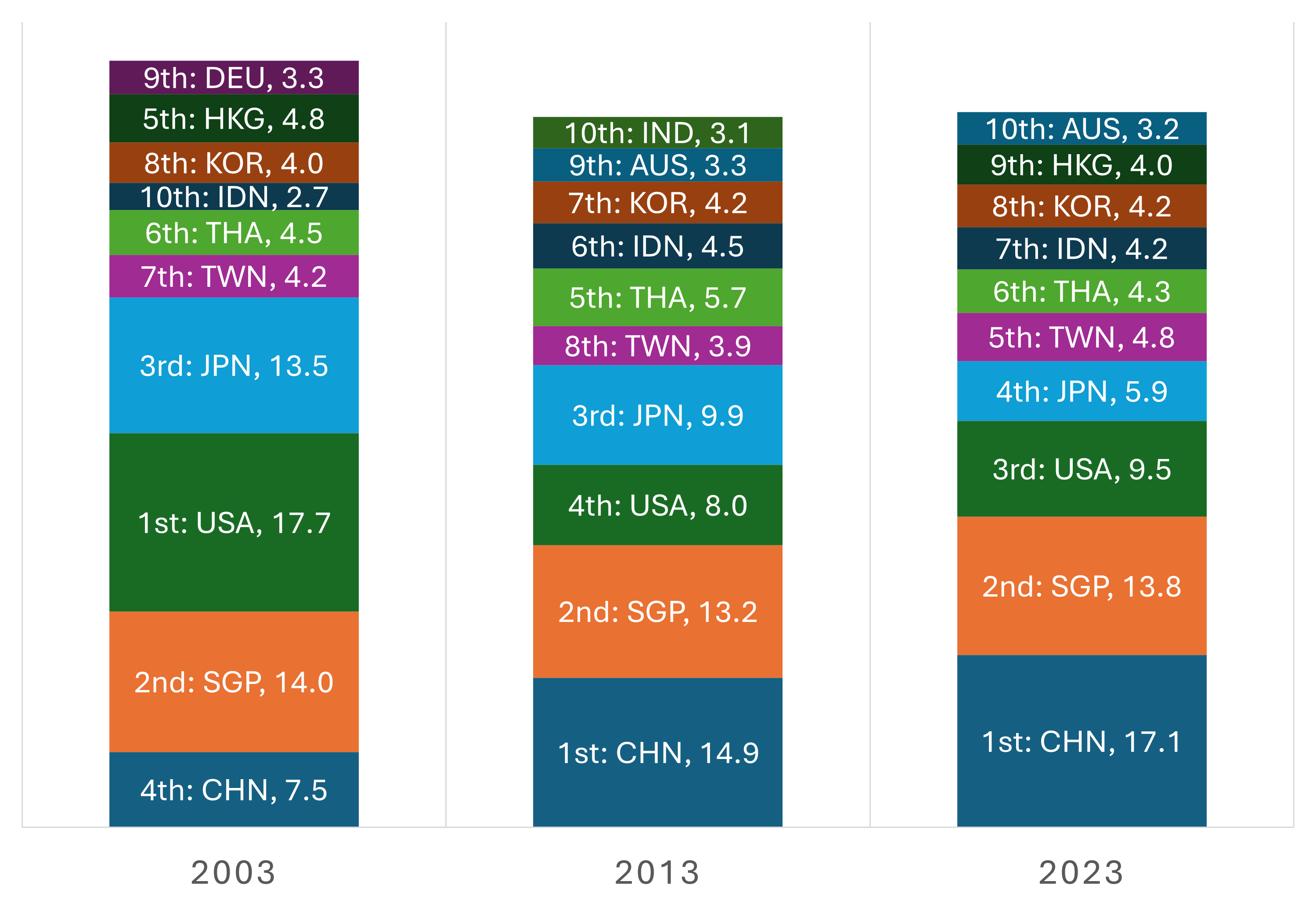

Looking further back, Malaysia’s trade has diversified. China’s role in Malaysia’s trade has grown since 2003, but today’s overall trade concentration is lower than two decades ago (Fig. 2). For one, China’s current trade share is below that of the United States back in 2003, when the latter was Malaysia’s top trading partner. Furthermore, Malaysia’s five largest trading partners now account for 51 percent of total trade, down from 58 percent in 2003.

Figure 2: Malaysia’s top 10 trading partners and their relative share of total Malaysian trade (%), 2003-2023. Source: Author’s calculations based on U.N. Comtrade (2024). Three-digit country codes reflect ISO 3166 standards.

Malaysia’s trade intensity with China is close to ASEAN’s average of 16 percent, and well within one standard deviation of the global average of 13 percent. Based on data sourced from the U.N. Comtrade database, 40 other economies, including Australia (29 percent), Indonesia (25 percent), Japan (20 percent) and South Korea (22 percent), have a significantly higher trade reliance on China (Fig. 3), but concerns over perceived economic alignment with Beijing rarely extend to these cases.

Figure 3: Countries by relative share of trade with China (%), 2023. Source: Author’s calculations based on U.N. Comtrade (2024)

Sectors and Sensibilities

The argument that Malaysia is overdependent on trade with China is even less compelling at the sectoral level, as some industries interact more with Chinese firms than others.

According to U.N. Comtrade data, Malaysia’s six largest industry/commodity sectors by trade value in 2023 are electrical machinery and equipment (33 percent of total Malaysian trade), mineral fuels (18 percent), machinery and mechanical appliances (9 percent), scientific instruments (4 percent), fats and oils (3 percent), and plastics (3 percent).

China is Malaysia’s largest trading partner in only three of these six sectors, with varying trade intensities. For plastics, China is the primary import source, accounting for a quarter of sectoral trade, over twice that of the next partner, Singapore at 11 percent. In machinery and mechanical appliances, 22 percent of trade involves China, with Singapore second at 15 percent. For electrical machinery and equipment, China leads at 19 percent, but Singapore (16 percent) and the U.S. (14 percent) follow closely, showing no significant overreliance on China in this strategic sector.

In the three other sectors – mineral fuels (mainly petroleum), fats and oils (mostly palm oil), and scientific instruments – China’s trade footprint is smaller. For fuels, China ranks fourth (9 percent), at half the value of Malaysia-Singapore trade. In fats and oils, Malaysia exports more to India than to China. For scientific instruments, the U.S. ranks first (22 percent), with China second (14 percent).

This sectoral breakdown shows minimal evidence of an unhealthy trade dependence on China. While claims of overreliance are often vague, the data largely suggests that Malaysia has avoided putting all its eggs in the Chinese basket thanks to a diverse mix of partners and products. China’s primacy is observed only in plastics, a sector affected by global concerns over Chinese overcapacity, an issue Malaysia is attempting to address through trade remedies, as discussed below.

Beyond Trade

Claims of “overdependence” also extend into areas beyond trade like FDI. Concerns revolve around China’s stake in Malaysian infrastructure projects through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). This line of argument is two-fold: first, that China is Malaysia’s biggest investor; and second, that BRI-linked FDI perpetuates “debt-trap diplomacy” among partner countries like Malaysia.

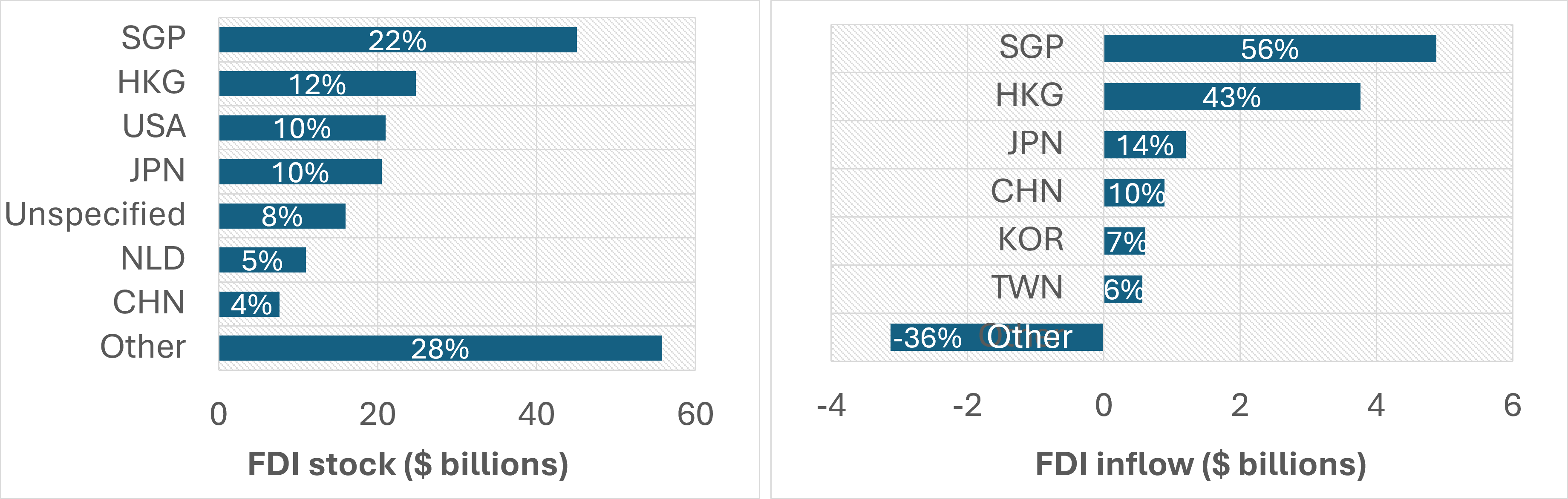

These claims do not align with the facts. China is not Malaysia’s main source of FDI. As of 2023, China’s FDI stock in Malaysia was $7.6 billion, less than 4 percent of the total, well behind Singapore, the U.S., and Japan (Fig. 4a). China’s annual FDI inflows to Malaysia meanwhile amount to just $900 million for the same year, compared to the national total of $8.8 billion (Fig. 4b). In short, Chinese investment constitutes a modest part of Malaysia’s FDI portfolio.

Figures 4(a) and (b): Malaysia’s FDI stock (left) and inflows (right) by source country and share ($ billions), 2023. Source: ASEANstats (2024)

Additionally, Malaysia’s external debt owed to China is minimal, estimated at 0.2 percent of GDP in 2017. Analysis of AidData’s 2023 Global Chinese Development Finance dataset also indicates that the majority of Chinese projects in Malaysia involve private players or government-linked corporations (GLCs) motivated by commercial considerations.

Corroborating this, a Chatham House report finds no evidence of Chinese geoeconomic maneuvering through the BRI. Indeed, Malaysia initiated most BRI projects and has renegotiated some to suit changing domestic priorities, as with the $16 billion East Coast Rail Link. Fundamentally, this signifies Malaysian agency in trying to maximize the BRI’s benefits consistent with domestic interests rather than any undue influence from Beijing.

Finally, the “debt-trap” narrative presupposes that Chinese investment is inherently problematic. Far from it, last year’s approved Chinese FDI alone is expected to create over 10,000 new jobs for Malaysians in the years to come, according to the Malaysian Investment Development Authority. In addition, the International Monetary Fund judged the country’s external debt to be “manageable” in its March 2024 macroeconomic assessment, countering the debt-trap concerns.

Agency in Action

The overdependence camp also claims time and again that Malaysia is “too deferential” to China, which overlooks Malaysia’s use of trade remedies and safeguards in line with the multilateral rules-based order. As of the end of 2023, Malaysia had more antidumping measures in place against China than against any other country, mainly duties on certain steel products, consistent with recurring concerns about Chinese overcapacity. In August 2024, Malaysia’s Ministry of Investment, Trade, and Industry opened a probe into plastic imports from China and Indonesia over alleged dumping. Any accusation that Malaysia kowtows to Chinese economic interests therefore ignores Malaysia’s agency in prioritizing national interests when these are at odds with Chinese actions.

Agency extends to Malaysia’s pragmatic pursuit of broad global economic partnerships. Relations with China do not preclude engagements with other countries, as seen in Malaysia’s participation in economic frameworks such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the U.S.-led Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, which do not involve China. Similarly, Malaysia’s acceptance of BRI does not impede its support for other initiatives, like the European Union’s Global Gateway. The $16 billion Lumut Maritime Industrial City project, for instance, is expected to benefit from EU investment. With the U.S., Malaysia has a memorandum of cooperation on semiconductor supply chain resilience, reinforced by its standing as the largest source of American semiconductor imports.

Agency is also reflected in intensified efforts to diversify trade through greater South-South cooperation, beyond Malaysia’s headline-grabbing BRICS membership application. For example, Malaysia has formalized a bilateral Joint Trade Committee with Brazil, agreeing to strengthen semiconductor and energy collaboration. With India, relations were upgraded in August to a comprehensive strategic partnership, encompassing greater government and business engagement. Moreover, as the upcoming ASEAN chair, Malaysia has also highlighted its interest in championing growth in intra-ASEAN trade.

Malaysia’s implicit geoeconomic strategy therefore demonstrates a balanced approach, avoiding alignment with any single power, whether China or the U.S.

The Overdependence Myth

At the end of the day, reports of Malaysia’s overdependence on China have been greatly exaggerated. Vague and poorly defined, these claims unravel upon close examination of bilateral and multilateral trade and investment data. Relatedly, there is a flawed tendency to misconstrue Malaysia’s strong ties with China as an unbridled embrace of Beijing, which is perceived to come at the expense of Washington or Brussels. This reasoning overlooks the economic cooperation that Putrajaya has established with myriad global partners. It also fails to recognize Malaysia’s agency in safeguarding its economic interests.

Ultimately, Malaysia’s strategic positioning transcends simplistic zero-sum narratives, showcasing its ability to engage China without pivoting away from either the West or the rest. Instead, it reflects the geoeconomic realities of a highly open economy navigating a complex, interconnected world.