As China surrounds Taiwan with warships, it’s time to consider what military operations Xi Jinping may be preparing for. This first part of a two-part series, based on the Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute’s new edited conference volume, “Chinese Amphibious Warfare: Prospects for a Cross-Strait Invasion,” distills key findings from the book, covering history and doctrine, China’s joint amphibious force, and its supporting enablers.

In what is also a warning to the incoming Trump administration, Beijing pressured Taipei with military exercises yet again this week, along new dimensions. This latest iteration of China’s all-domain pressure campaign involved deployment of many government-controlled vessels from China’s Navy, Coast Guard, and “civilian” sector in the East and South China Seas: waters near Taiwan and Japan’s southwest islands, with unprecedented coverage of the First Island Chain.

There, according to Taiwan Defense Ministry spokesman Sun Li-fang, China undertook its largest maritime operations since 1996. Roughly 60 naval warships, 30 Coast Guard vessels, and several thousand personnel were directly involved. China has “extended their military strength outward,” senior Taiwan Defense Ministry official General Hsieh Jih-sheng told reporters. “The numbers are indeed astonishing.”

Seven “temporary reserved areas” of airspace east of Fujian and Zhejiang provinces also allowed for military aerospace operations. On December 9 alone, Taiwan’s Defense Ministry reported, 47 People’s Liberation Army (PLA) aircraft were active around Taiwan, 16 of which crossed the Taiwan Strait’s median line and entered Taiwan’s air defense identification zone (ADIZ).

My quarter-century of watching China’s military coincides with its most concerted ramp-up, yet never have I seen so many trendlines converging so concerningly as is happening of late. China is engaged in the most dramatic military buildup since World War II, constantly adding staggering quantities of advanced weapons, and training relentlessly to employ them effectively.

To maximize his historical legacy, paramount leader Xi Jinping clearly covets the ultimate geopolitical prize: Taiwan, the last redoubt of flourishing freedom in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)-claimed sphere. Xi can still be deterred from invading Taiwan, but the scope for doing so is decreasing precipitously. Time is running short, and the stakes could scarcely be higher.

That is why it is vitally urgent to understand what Xi’s ultimate move to take Taiwan might look like, and to double down on defenses to deter him from ever attempting it – by far the best outcome for all concerned.

To that end, the Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI) has just published its eighth edited conference volume, “Chinese Amphibious Warfare: Prospects for a Cross-Strait Invasion.” (Access a free full-text PDF here.) CMSI’s findings are nuanced but bracing. Previously limited in ability to conduct joint firepower strike, blockade, and island landing campaigns against Taiwan, China’s military is making rapid progress across the board as it prepares to meet the requirements of Xi’s Centennial Military Building Goal – a development deadline to give him a full toolkit of Taiwan-relevant military operational capabilities by 2027.

Drawing on research, writing, and insights from some of the world’s leading experts, CMSI’s latest book offers something for everyone interested in these vital subjects: gripping historical narratives, cutting-edge analysis, numerous graphics and data tables, and an appendix detailing the major warships and landing craft in China’s amphibious order of battle with exquisite ship silhouettes and specifications. This volume probes key questions: How might China’s armed forces attempt to execute its Joint Island Landing Campaign to achieve a cross-strait invasion of Taiwan? What might be its prospects for success, and what must Taiwan – with U.S. support – do urgently to shore up deterrence?

Since CMSI’s founding two decades ago (internally in 2004, externally in 2006), its principles have included focusing on the People’s Republic of China (PRC)’s military maritime development – across the waterfront, far beyond naval affairs alone. We believe that rigorously analyzing pedigreed Chinese-language open sources offers unique insights, particularly through surveying PRC thinking and discerning inner layers indirectly, as well as through probing frontier intangibles. This is how CMSI has approached every conference and resulting volume, including this one on large-scale amphibious warfare in PRC military strategy.

A Brief History of the PRC’s Amphibious Warfare

As CMSI drilled deep into related topics and considered who could best address them, we already knew that Mao Zedong had ordered the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to prepare for an amphibious attack on Taiwan in summer 1950, before U.S. intervention following the Korean War’s outbreak that June thwarted his plans. My own personal contacts, for instance, had shared family accounts of relatives in China’s military who were in the process of being called up then to participate in a cross-strait invasion. We hoped to figure out how to keep the CCP’s plans perpetually thwarted in this regard.

Part 1 of our book, “Doctrinal Foundations of Chinese Amphibious Warfare,” thus illuminates foundational history that informs today’s PRC amphibious doctrine and otherwise shapes what we now confront. Grant Rhode chronicle’s Admiral Shi Lang’s invasion of Taiwan in 1683 – far removed from modern military operations but leveraged symbolically and politically by Beijing in recent years.

Xiaobing Li, a renowned historian who himself earlier served in the PLA, surveys its formative experiences in amphibious warfare. Devastating failure in attempting to take Kinmen in October 1949 yielded lessons that facilitated the PLA’s dramatic success in the April 1950 Hainan Island landing. That victory, in turn, inspired China’s leadership to subsequently prepare for a similar assault on Taiwan. Premier Zhou Enlai officially postponed the operation at the end of the planned landing window, June 30, 1950, because the Korean War had triggered U.S.intervention earlier that month.

Despite the U.S. Seventh Fleet’s command of the Taiwan Strait, which it would pacify with its Formosa Patrol for the next 29 years, China’s leadership did not relinquish this goal easily; the Central Military Commission subsequently instructed that 1952 would be the earliest window for an attack on Taiwan. Pursuit of that ultimate prize was reluctantly postponed indefinitely, and has only resurfaced realistically in Xi’s bold “new era.”

For the remainder of the 1950s, with regard to Taiwan, the PLA shifted its focus to capturing small, nearby Kuomintang (KMT)-held offshore islands “piecemeal” in ways that would not trigger U.S. intervention. It succeeded in wresting the Dachens, including through its iconic “joint” battle at Yijiangshan. Despite initiating the 1954-55 and 1958 Taiwan Strait crises, however, China could not capture the Kinmen and Matsu archipelagos. The Dwight D. Eisenhower administration’s threat of intervention and potential use of nuclear weapons proved a credible deterrent. Unfortunately, as Admiral Michael McDevitt warns in his chapter, U.S. presidents face a far more powerful PRC today than Eisenhower ever did.

China’s Amphibious Warfare Doctrine

Nevertheless, as Christopher Yung and Zoe Haver relate, PLA amphibious doctrine has its origins in preparations beginning in 1949 to take Hainan the following spring, and aborted preparations to take Taiwan under Mao’s favored General Su Yu. Su grappled with embryonic versions of the problems confronting his successors today: providing air cover, achieving maritime superiority, and mustering sufficient sealift.

For militaries, it all starts with doctrine: the fundamental set of principles by which military forces or elements thereof guide their actions in support of national objectives. In plain English: what they are supposed to do, and how they are supposed to do it. We naturally wanted to frame our analysis by investigating what China’s leadership has tasked its military with achieving to execute amphibious operations, and how its military plans to go about it.

Yung and Haver lead off with six key pillars of PLA amphibious doctrine, which reflect “gold standard” principles developed by the United States and its allies during World War II: (1) dominance of the three domains (air, sea, and information), (2) key-point strikes, (3) concentration of “elite strengths,” (4) rapid and continuous assaults, (5) integrated and flexible support operations, and (6) psychological attacks.

To understand how China seeks to apply its doctrine specifically regarding Taiwan, we examine the Joint Island Landing Campaign – the PLA’s main operational concept for cross-strait invasion. Primary objectives are penetrating Taiwan’s coastal defenses and securing a lodgment to facilitate further offensives to seize and hold key targets. Multiple subcampaigns require intense joint combat involving all PLA service arms. Phases include (1) preparatory operations, (2) assembly, embarkation, and transit, and (3) landing and beachhead establishment.

China’s Joint Amphibious Force

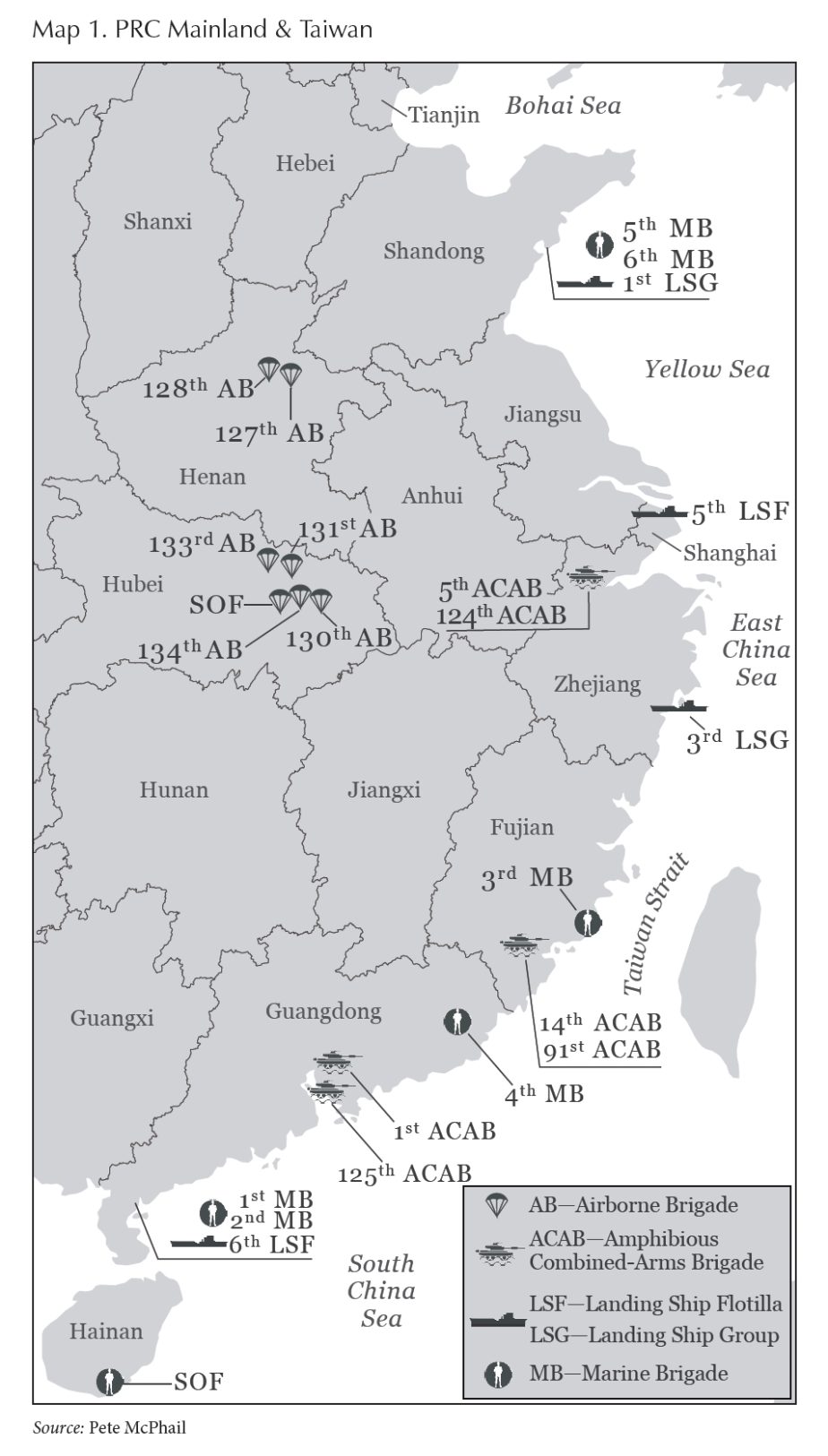

China’s joint amphibious force has four main components: the amphibious units of the PLA Ground Forces (PLAGF); the PLA Navy Marine Corps (PLANMC); the PLA Navy (PLAN) amphibious fleet; and the civilian support fleet.

Part 2 covers “The Joint Amphibious Force.” Dennis Blasko surveys the PLAGF’s amphibious components, which represent the bulk of PLA sealift in the form of six Amphibious Combined-Arms Brigades. He assesses that reforms have rendered these units possibly capable of seizing Taiwanese offshore islands, but limitations in training and readiness leave them short of being able to lead a successful assault on Taiwan’s main island – the ultimate objective. A question debated but unresolved by our contributors is whether China might preemptively threaten or conduct strikes against, or seizure of, offshore islands short of attempting to invade mainland Taiwan.

Conor Kennedy investigates China’s Marine Corps, which has more than tripled in size since 2017, expanding from approximately 10,000 personnel to over 30,000, with a corresponding increase in brigades from two to eight. While the PLANMC is in large part an expeditionary force charged with protecting China’s “overseas interests,” it would have key roles in a Taiwan invasion: advance operations to create favorable conditions for landing operations, as well as smaller landing initiatives of its own in support of the larger campaign. Follow-on efforts beyond the beachhead could include urban warfare.

Jennifer Rice reviews the PLAN amphibious fleet. Its prioritization of larger amphibious ships suggests an emphasis on overseas operations similar to that of the PLANMC. With the world’s largest shipbuilding industry, China could surge production of smaller single-mission Landing Ship, Tank (LST) and Landing Ship, Medium (LSM) vessels optimized for a Taiwan invasion, but has yet to do so. On this basis, several other authors maintain that China will likely be unable to conduct a large-scale cross-strait invasion successfully until it masters what the U.S. military terms “joint logistics over the shore.”

By contrast, Lonnie Henley argues that using numerous Maritime Militia and militia-crewed “civilian” vessels to fill this gap in amphibious sealift, logistics, and matériel is in fact not a bug but a deliberate feature of how China’s armed forces are preparing cross-strait capabilities. It fits with formative PLA battle experiences, including in capturing offshore islands from the KMT. It is a tempting way to leverage the extraordinary range and resources of China’s maritime sector, including its civilian components.

All told, it is a potent example of why U.S. planners must consider the possibility of Beijing improvising in “just-good-enough-for-long-enough” fashion to attempt to pursue core political objectives, particularly if events or trend lines “force” Xi’s hand. But this stopgap approach brings manifold vulnerabilities for China. It is challenging to apply regulations and management consistently in practice, including constantly updating the inventory of ships and crew and ensuring their readiness. The vessels and their communications are highly exposed in ways which we and our allies and partners can target with a battery of countermeasures.

Other forces would be vital to a cross-strait campaign even without participating in the main invasion force. That is the focus of Part 3, “Enablers of Amphibious Warfare.” For example, Cristina Garafola covers a key PLA Air Force (PLAAF) component: the PLA Airborne Corps. Its paratroopers operate from various aircraft, including the PLAAF’s Y-20 transport. As with most of the PLA, the Airborne Corps has improved through persistent reforms. However, as Garafola and other contributors discuss vigorously, it remains uncertain how effectively the Airborne Corps would support a Taiwan invasion. Some of the greatest questions center on how well it would coordinate with other arms and services, particularly in the complex, confusing conditions of an actual landing operation.

Whereas Garafola examines fixed-wing-delivered forces, Tom Fox focuses on rotary wing possibilities – specifically the PLAGF’s helicopter units. While some outside CMSI have speculated that helicopters could offer a major source of cross-strait force delivery, Fox draws on his own helo-pilot experience and analytical expertise to identify limitations in training and readiness. Even using virtually all available PLAGF helicopters would not likely be able to overcome Taiwan’s defenses and compel capitulation. Even if pilots could be forced to accept terrible survival odds, a sudden two-wave attack (older helos first, newer helos second) would likewise probably fail. Helicopters thus currently offer no “easy button” to conquer Taiwan.

John Chen and Joel Wuthnow probe PLA and People’s Armed Police Special Operations Forces (SOF). As a learning organization lacking successful amphibious experience in recent decades, China’s armed forces are transferring and reverse-engineering history, drawing on foreign examples to inform their development. PRC analysts regard the 1982 Falklands campaign as a model for how British SOF collected intelligence and conducted confusing, disruptive raids to help the main force of Royal Marines and 2nd Battalion, the Parachute Regiment (2 Para) land with little resistance. They likewise view the United States’ 1983 Grenada campaign as a model for SOF strikes and raids.

Accordingly, SOFs from China’s Ground Forces, Navy, and Air Force would play important roles in the preparatory and main-assault phases of an amphibious invasion, including reconnaissance and targeting, clearing obstacles, conducting strikes and raids, and performing extraction missions. Employing advanced equipment and coordinating with other forces could prove difficult in practice.

Thomas Shugart covers one of the most unsung but critical amphibious elements: mine warfare. He estimates that China has the world’s most potent at-scale mine delivery, from submarines, aircraft, and surface ships – including Maritime Militia vessels. Prior to attempting an invasion of Taiwan, China’s military would likely endeavor to blockade Taiwan with sea mines. Doing so would be challenging, and invite severe countermeasures – including use of naval mines against China. While China’s mine countermeasures forces include new minesweeping vessels and mine-hunting robots, finding and neutralizing mines is slow and difficult for even the most capable of militaries.

This first part of a two-part series has summarized key findings from “Chinese Amphibious Warfare” in the areas of the PRC’s amphibious history and doctrine as well as its current joint force and its supporting enablers. Part 2 will offer larger implications from the book’s penultimate and concluding sections, and spotlight ongoing research areas.