Jimmy Lai, the self-made billionaire and founder of Hong Kong’s Apple Daily, is on trial under the city’s National Security Law. The trial has been agonizingly slow – it began on December 18, 2023 – but Lai has been in prison even longer. December 31 will mark four full years in continuous detention.

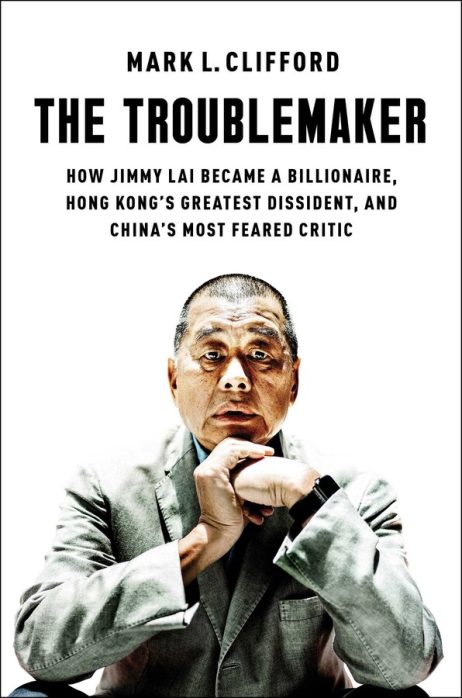

Lai has become Hong Kong’s most famous prisoner of conscience. In a new biography, Mark L. Clifford, a journalist who worked with Lai during his time as board directors at Next Digital, details the extraordinary life of Jimmy Lai. In “The Troublemaker: How Jimmy Lai Became a Billionaire, Hong Kong’s Greatest Dissident, and China’s Most Feared Critic,” Clifford details Lai’s days of extreme poverty in Guangdong and his rags-to-riches rise after arriving in Hong Kong. Along the way, Lai became a deep believer in freedom and founded Hong Kong’s most widely read pro-democracy paper. His advocacy eventually led to his arrest, but Lai continues to remain defiant, even taking the stand as a witness in his trial.

“Jimmy Lai’s life story is the story of Hong Kong,” Clifford told The Diplomat in an interview. “…Hong Kong gave Jimmy Lai freedom and he often said that he owed the city everything.”

Jimmy Lai was born in China’s Guangdong Province but moved, alone, to Hong Kong at the age of 12. Where do you think he would fall on the identity spectrum, to use the categories from the long-standing (and now discontinued) Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute survey: Hong Konger, Hong Konger in China, Chinese in Hong Kong, or Chinese?

He is first and foremost a Hong Konger. Hong Kong gave him everything – first food, then freedom, later his family, and finally his faith. Hong Kong is where he learned what he always calls “Western values,” which he says start with rule of law – the idea that everyone is equal before the law, an idea that he credits to British colonialism. He is also British – he has had British citizenship since 1992. He’s never had a Chinese passport – the last time he traveled on Chinese papers was when he left the country in 1961 – but he is of course also Chinese. Jimmy Lai is a proud and patriotic Chinese man who has been broken-hearted at the country’s backpedaling on reform after the promise of the early 1980s, of the early Deng Xiaoping “reform and opening” years.

Lai, like many overseas observers, was convinced in the 1990s that the CCP’s days of ruling China were numbered. How did this belief intersect with his decision to run an outspoken pro-democracy media outlet? Did Lai eventually come to change his mind on the CCP’s future?

He thought that his publications could contribute to continued economic and, someday, political reform on China. In the 1990s, and even later, he thought that reform would come soon and that the days of totalitarian Chinese rule would end. He admits that he was far too optimistic – and came to see that Xi Jinping’s use of technology gave him a power over society that even Mao had not enjoyed. But he continued to believe that freedom would prevail and that the internal contradictions of the Chinese Communist system would be its downfall. As a businessman and a believer on the free market, he understood that Xi’s crackdown on the private sector would hobble the Chinese economy. In my last conversations with him, shortly before he went to jail in 2020, Lai still believed that a collapse would come, partly because of the endemic corruption in the Chinese communist system.

What explains Lai’s continued faith in advocacy and activism, even as the CCP began to clamp down on Hong Kong’s freedoms, especially after the 2014 Umbrella Movement?

What explains Lai’s continued faith in advocacy and activism, even as the CCP began to clamp down on Hong Kong’s freedoms, especially after the 2014 Umbrella Movement?

Lai isn’t driven by expediency. He is driven by principle. He is stubborn, a self-described “troublemaker” in the sense immortalized by iconic U.S. civil rights activist John Lewis, of making “good trouble.” Hong Kong gave Jimmy Lai freedom and he often said that he owed the city everything. He is all about freedom – economic freedom, political freedom, spiritual freedom. He told associates that he would rather be hanging, dead, from a lamppost in Central than to give the Chinese Communist Party the satisfaction of saying he ran away. That’s his character.

Lai’s Apple Daily today is best remembered as a pro-democracy newspaper, thanks to its prominent coverage of the protest movements in 2014 and 2019. But it was also very much a tabloid, with celebrity gossip and at times, questionable journalistic ethics. Do you think Apple Daily’s approach of “selling freedom” – with clear profit motives – undermined its reputation as a pro-democracy publication?

No, not meaningfully. In its early years, Apple Daily went to the edge of good taste and sometimes beyond. Lai and his team of journalists learned from their mistakes and pulled back from the most salacious coverage. After 2003, when Apple Daily and Next played a key role in bringing out 500,000 people to demonstrate against National Security Legislation, there wasn’t any question about its commitment to Hong Kong’s democracy movement. In fact, something different was at play, because many people – especially younger ones – felt that the paper was too timid, too moderate in its embrace of democracy. Lai’s strong and principled commitment to non-violence and his rejection of calls for Hong Kong independence may have cost the paper sales, but reflected Lai’s philosophy.

What does the span of Lai’s career – from factory worker to billionaire to political prisoner – tell us about Hong Kong’s own evolution from the 1960s to today?

Jimmy Lai’s life story mirrored a Hong Kong that in a generation was transformed from shantytowns inhabited by refugees like Lai to one of the world’s wealthiest cities. He came as a hungry teenager, smuggling himself into Hong Kong to escape famine in China, a famine that killed some 45 million people. In Hong Kong he first found the freedom to make money – and the freedom to eat. Later, he took advantage of the free-wheeling British colony’s economic freedom to start his own business and become wealthy. Still later Lai latched on to the promise of expanding political freedom in the last years of British rule to launch his media empire. Finally, the jailing of Lai exemplifies the crushing of freedom following the 2019 summer of democracy. His embrace of the Catholic religion, and the denial of Holy Communion for him in recent months, also bears witness to a long tradition of religious freedom and a vibrant community of believers, but one that is today under unprecedented pressure from communist authorities. Jimmy Lai’s life story is the story of Hong Kong.

Lai put great stock in the potential for international pressure to change CCP and Hong Kong government policies. That faith is in part what led to his arrest on charges of “conspiring to collude with foreign forces.” How can the international community best support Lai now, as he faces a lengthy prison sentence pending the conclusion of his ongoing trial?

First, just keep saying Jimmy Lai’s name. Keep the spotlight on him. Politicians and government officials, backed by media and civil society, need to help Xi Jinping understand that Jimmy Lai is more trouble in prison than out. We need to keep up the pressure on Hong Kong – where government officials are trying to pretend that the destruction of a free city didn’t happen. Western financial firms whose senior executives attend the Hong Kong government’s annual financial conference need to be shamed for their part in enabling a regime that has locked up more than 1,900 political prisoners in the past five years. We need to raise the cost to China and Hong Kong for holding Lai.

At the same time, Beijing needs to understand that there is an exit ramp that would lead to easing the pressure on Hong Kong and China’s faltering economies. China likely would demand that sanctions be lifted on Hong Kong officials in return.

It’s encouraging that President-elect Donald Trump promised that he would “100 percent” get Lai out of prison. It’s also notable that British Prime Minister Keir Starmer publicly brought up Lai’s imprisonment in a recent meeting with Xi Jinping.

Jimmy Lai does not aspire to political leadership and Apple Daily’s presses are not going to start rolling again. It’s time for this aging man to be allowed to spend his final years peacefully with his family. Beijing should understand that nothing else would pay higher dividends for a lower cost than letting Lai out of prison. China would give Trump a win that would cost it little.