In their quest for economic growth and energy security, China and India share the interest of reliable, seamless connectivity with Central Asia. To pursue this interest, Beijing and New Delhi have embarked on major initiatives to bolster their linkages with the five Central Asian states. A scrutiny of the data reveals that despite the shared interests and ambitions, China’s and India’s economic footprints in the region differ significantly. China has substantially strengthened its clout in the region over the years, while New Delhi’s presence remains muted due to limitations in state capacity, geography, and strategic preferences.

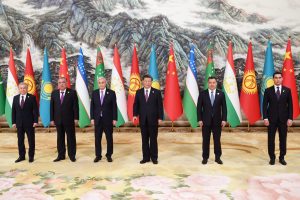

China and India are among the biggest economies in the world. To sustain their growth, they need dependable, diversified access to external markets and energy resources. Central Asia emerges as a crucial partner in the Sino-Indian pursuit of economic development, as it was reiterated at separately organized summit meetings between China, India, and the five Central Asian states in 2022.

The collective population of the five Central Asian states – Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan – is close to 80 million, with increasing consumer demand, entailing business opportunities. The area is situated in a geostrategic location that connects Europe with Asia, nestled between major powers like Russia, China, and India. Furthermore, Central Asia holds more than 4 percent of some of the world’s key resources, such as oil, gas, and critical materials.

Against this backdrop, Central Asian states can become invaluable trade partners, trade conduits, and energy suppliers to China and India. To double down on those commercial opportunities, Beijing and New Delhi set out policies aimed at strengthening their ties to Central Asia.

India, which considers the region to be its “extended neighborhood,” proposed the “Connect Central Asia” policy during Minister of State E. Ahamed’s visit to Kyrgyzstan in 2012. The initiative aims to enhance security, political, economic, and cultural ties between India and Central Asia. India pledged to cooperate with the Central Asian republics in a variety of fields, such as resources, steel production, air and land connectivity as well as banking.

In a similar fashion, China also reached out to Central Asia in an effort of enhancing connectivity to overseas markets. President Xi Jinping proposed the “Silk Road Economic Belt” (SREB), a massive connectivity program in 2013 during a state visit to Kazakhstan. The SREB is the land-based pillar of China’s “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI), that combines various forms of connectivity to deepen international relations and trade. At present, the number of participating countries exceeds 150, including states from Europe, Africa, Asia, Oceania, and the American continent.

Despite their shared interests and ambitions regarding Central Asia, there are stark differences between China’s and India’s economic footprint in the region.

China consolidated its ties to Central Asia by completing various connectivity projects. The Khorgos Gateway, a container terminal in Kazakhstan, opened in 2015, facilitating land transportation between China and Europe. Today, China and Kazakhstan are linked via at least five oil and gas pipelines, railway trunk links, and an International Border Cooperation Center. In Uzbekistan, the China Railway Tunnel Group completed the Qamchiq Tunnel in 2016, which is a part of the Angren-Pap railway line.

China’s commitment to large-scale infrastructure projects led to a steady expansion of investment in the region. According to aggregated data from Central Asian statistical and bank authorities, China’s investments into Central Asia surpassed $1 billion in each year during the 2018-2023 period, and in 2023 amounted to approximately $2 billion. This makes China a top foreign investor in the region, along with the Netherlands, the United States, Russia, and Switzerland. China has been Tajikistan’s biggest source of foreign investment for at least five years, and Chinese investments represented approximately 7 percent of Kazakhstan’s gross direct investment inflows in 2023.

China-Central Asia commercial ties also deepened through the years. China’s two-way trade with Central Asia more than doubled from $41 billion in 2018 to nearly $90 billion in 2023. This represents roughly 1.5 percent of China’s total trade, a share that is comparable to that of France, which is Beijing’s third biggest trade partner in the EU. China has been a top trade counterpart of Central Asian countries for years and became Kazakhstan’s biggest commercial partner in 2023.

In contrast, New Delhi’s footprint in the region is characterized by partial achievements. 2017 marked the inauguration of the first phase of Iran’s Chabahar port, an India-supported connectivity node that allows New Delhi to reach Central Asia through Afghanistan. In 2018, New Delhi joined the Ashgabat Agreement, enabling it to collaborate with Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Kazakhstan, among others, to deepen connectivity between Europe and Asia. In 2022, the eastern section of the International North-South Transport Corridor – a multimodal logistics route connecting India with Russia – started operating, delivering goods via Central Asia.

Regardless of these preliminary results, India’s investments in the region are merely a fraction of China’s. In 2018, direct investment flows from India to Central Asia surpassed $45 million, but they slowed down to approximately $30 million in 2023. Kazakhstan is a key destination of Indian investments within Central Asia, but in 2023, India was not among the top 30 sources of gross foreign direct investment inflows there. India ranks slightly higher as a foreign investor in Kyrgyzstan, but it lags far behind China and other key players like Russia or the United States.

Just as its investments, India’s trade with the region has long been operating below potential. For instance, New Delhi’s actual trade turnover with Central Asia in 2015 was six to ten times below potential, according to calculations based on a gravity model of trade. The trend persists to this day. In the period between 2018 and 2023, India’s two-way trade with Central Asia was around $1-3 billion per year, and it even declined recently. In 2023, India’s trade turnover with Central Asia barely exceeded $1 billion, representing less than 0.5 percent of India’s total trade, and only a fraction of China’s aggregate commerce with the region.

The pronounced differences between China’s and India’s economic presence in Central Asia are rooted in three factors: state capacity, geography, and competing strategic imperatives.

In terms of state capacity, China is the second biggest economy of the world with vast financial resources at its disposal. As it seeks to diversify its commercial routes to Europe to strengthen linkages with its key trade partners like Germany and France, Beijing can leverage those resources and rely on its massive network of state-owned enterprises to implement the BRI.

While India is among the fastest growing economies of the globe, it still lags behind China. When it comes to outbound investments, private companies act as dominant players in overseas financial activities. Such entities are more interested in profits than policy implementation, so financial flows gravitate toward developed economies rather than Central Asia. While India’s overseas investment profile is improving, it is yet to catch up with China in terms of scale and efficiency.

India’s state capacity challenge is compounded by the tyranny of geography when it comes to Central Asia. While China is a direct neighbor to Central Asia, India struggles to reach the market in the first place. Afghanistan, and an unfriendly Pakistan, sit between India and Central Asia, blocking direct access to the region.

India could mitigate these challenges by participating in China-funded projects. The BRI is an open-ended program and China has been trying to get India on board with it. India, however, has been reluctant to extend support to the BRI. On the one hand, the BRI’s flagship project, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC,) traverses through Kashmir, a territory under dispute between Pakistan and India, and the resulting sovereignty concern prevents India from getting on board with China’s initiative. On the other hand, India is concerned about the financial sustainability of BRI projects, further impeding New Delhi’s participation.

Long story short, Central Asia features prominently in the strategic calculus of China and India. China has a head start in terms of economic clout in the region. Given the strategic divergences in Sino-Indian relations, India’s initiatives of connecting to Central Asia are independent from China’s.

Central Asian states stand to benefit from this dynamic, as they can diversify their trade and investment partners to reduce their dependence on other powers, such as Russia or the United States. Recognizing this opportunity, Kazakhstan has already been leveraging its relationship with multiple major powers to cultivate its economic growth and independence. As the Sino-Indian pursuit for markets and energy unfolds, other Central Asian states may follow suit.