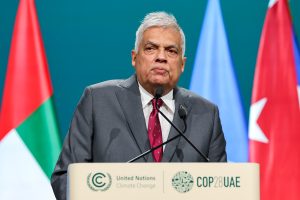

In late 2023, at the 28th session of the Conference of Parties (COP28) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), Sri Lanka’s then-President Ranil Wickremesinghe delivered a compelling speech that highlighted the urgent need to address climate change and its disproportionate impact on low-income countries. He stated, “We, the developing countries, are both disproportionately vulnerable and disproportionately impacted due to our lower adaptive capacity in terms of investments in finance, technology, and climate resilience.”

This address was notable, as it was the first instance in which a Sri Lankan president used a high-profile platform like the UNFCCC COP to advocate for accelerating climate finance for countries most vulnerable to the effects of climate change.

Sri Lanka’s Climate Diplomacy Moves

Alongside this, and thereafter, the Sri Lankan government has continued to play an active role in forging collaborations with developing countries to take a global position. On the sidelines of COP28, Wickremesinghe launched the “Tropical Belt Initiative,” a regional cooperation effort for countries that share common climate challenges, but also are rich in ecosystems that are globally significant for carbon sequestration.

Wickremesinghe’s initiative was ostensibly aimed at attracting investments into these ecosystems. He even mooted the idea that the West should offer debt relief to countries that commit to this initiative, or similar climate mitigation projects within the tropical belt. He suggested that the savings would support ecosystem restoration and rehabilitation of degraded sites in tropical regions, thereby contributing to the global fight against climate change.

This idea of debt relief to help finance climate ambitions was reiterated at a panel on “Greening the Belt and Road Initiative,” where Wickremesinghe advocated for debt relief for low-income countries to facilitate their green transitions. At the 10th World Water Forum, he went a step further by proposing a 10 percent levy on the annual profits of global tax evasion assets deposited in tax havens. He argued that the funds raised from this levy, estimated at $1.4 trillion per annum, could be used to support measures to combat climate change.

In May 2024, Sri Lanka joined the Global Blended Finance Alliance, which aims to strategically use development finance (such as public and philanthropic funds) to mobilize additional commercial finance toward sustainable development in developing countries.

While many of these may seem like overly lofty ambitions and pronouncements, international diplomats and notable players in the global climate finance landscape acknowledge that these remarks by the country’s leaders did help put Sri Lanka’s climate ambitions on the global map. It generated interest among peer developing countries and sent signals to international development organizations that this was a space that the country was interested in pursuing. Unfortunately, Sri Lanka lacked an institutionalized mechanism to follow up on these pronouncements, especially with the election of a new government last year. As a result, it has become unclear how the country would build on the gains made on the global stage and make meaningful progress in securing climate financing for itself and other developing countries.

This is an important agenda for the country’s future – not only to cope with ecological and climate pressures, but to ensure Sri Lanka’s economic recovery.

Nature and Climate Matter for Sri Lanka’s Recovery

Sri Lanka ranks 23rd out of 180 countries most impacted by extreme weather events, and estimates show that around 19 million Sri Lankans (over 90 percent of the population) live in locations that could become moderate or severe climate hotspots by 2050 under a carbon-intensive scenario. The country is also experiencing a shoreline retreat of 200,000 to 300,000 square meters per year, posing a threat to coastal livelihoods, tourism, and infrastructure. Sri Lanka is home to 66 critically endangered and 102 endangered animal species, and 156 critically endangered or endangered plant species, which are at risk from the impacts of global climate change.

Addressing these challenges will require new and additional sources of capital, given the severe strains on public finances and limitations on fiscal expansion.

Under its current IMF program, Sri Lanka is required to have achieved a primary fiscal surplus of 0.8 percent of GDP by 2024, and then increase the surplus to 2.3 percent of GDP by 2025. It must reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio from 128 percent in 2022 to 95 percent by 2032. While Sri Lanka’s economy has stabilized from the severe crisis of 2022, the pathway to sustained recovery remains precariously narrow.

The good news is that Sri Lanka is making steady progress toward debt sustainability, having secured agreements with official creditors, and completed the issuance of restructured sovereign bonds to commercial creditors. International ratings agencies have already raised the country’s sovereign rating out of default status.

The deal with commercial creditors includes a so-called Macro-linked Bond, which is a state-contingent instrument where the level of GDP and GDP growth by 2027-28 will determine different restructuring pathways from that point onward. Sri Lanka would be the experimental case for this type of restructuring, putting further focus on the quality and stability of growth over the forthcoming decade.

As such, climate shocks – such as changing rainfall patterns that affect the country’s agricultural and commodity export output, as well as hydropower generation and consequences for oil imports – will be a critical determinant of Sri Lanka’s growth pathway. Additionally, many of its key economic sectors, ranging from export products like tea, rubber, coconut, and spices to its recovering tourism services industry, are reliant on natural ecosystems.

Sri Lanka’s Climate Prosperity Plan estimates that $26.5 billion in investments will be required by 2030, with 69 percent allocated to mitigation efforts and 31 percent dedicated to adaptation actions. Additionally, the country requires $100 billion to become a net zero emitter by 2050.

Recognizing the Realities of Global Climate Finance

No doubt, the high-profile efforts noted earlier have helped in putting Sri Lanka on the global stage for climate financing, but securing those sources of funding will not be easy amid acute gaps and inequities in the global climate financing landscape. Notably, for debt-distressed countries like Sri Lanka, OECD data shows that 72 percent of international climate finance was made up of loans, with only one-quarter of it being in the form of grants.

According to an Independent High-Level Expert Group Report on Climate Finance, an estimated $1 trillion per year is required by 2030 for emerging markets and developing countries (excluding China) to establish adaptation and resilience mechanisms necessary to combat climate change. In 2009, developed countries committed to providing and mobilizing $100 billion of climate finance each year by 2020 through to 2025. But, studies have shown that only eight countries have contributed their fair share of the goal.

There is also much less finance available for adaptation (investments in infrastructure, technology, and practices designed to reduce vulnerability to climate-related hazards), compared to mitigation (investments to reduce or prevent greenhouse gas emissions, like renewable energy, and sustainable transportation). According to OECD assessments, out of the $115.9 billion raised in climate finance for developing countries in 2022, only $32.4 billion was raised for adaptation, compared to the $69.5 billion raised for mitigation.

The geographic concentration of climate finance will also matter. According to the Climate Policy Initiative, climate finance remains heavily concentrated in specific regions. The 10 countries most affected by climate change between 2000 and 2019 received less than 2 percent ($23 billion) of total climate finance. Emerging markets and developing economies and least developed countries, which are disproportionately vulnerable to climate change despite not being major historical emitters, face the most significant funding challenges.

Laying the Domestic Groundwork

Even as the global landscape remains uneven and unjust, Sri Lanka has begun preparing its own groundwork for accessing and managing these new sources of prospective funding. The Central Bank has developed a Roadmap for Sustainable Finance, which guides banks and non-bank financial institutions and outlines key actions these institutions must take to promote and develop green financial products. An update to the Roadmap is expected later this year.

The Central Bank also released a Sri Lanka Green Finance Taxonomy, which helps classify economic activities that can be considered environmentally sustainable. It is intended to assist financial market actors seeking to raise capital for green activities in local and international financial markets and deploy them credibly in domestic projects.

The Ministry of Finance is nearing the completion of the country’s first Green Bond Framework, designed to help raise sovereign green finance from international capital markets, useful for a return to capital markets after 2027. Meanwhile, the Colombo Stock Exchange has introduced the listing and trading of Green Bonds, and since then several banks have raised money using this instrument. The proceeds from green bonds are expected to be exclusively invested in projects that generate climate or environmental benefits.

Priorities for the New President

In recent years, Sri Lankan leaders’ proactive stance on climate finance in global fora has reflected a new urgency in making a transition to a green economy, even as it was ostensibly also aimed at sourcing new development financing following the country’s economic crisis and debt default. As Sri Lanka grapples with macroeconomic, environmental, and growth challenges, substantial investment in both mitigation and adaptation actions will undoubtedly be needed.

Sri Lanka’s new president, Anura Kumara Dissanayake, and his National People’s Power coalition have made powerful references to charting a more sustainable growth path. Their election manifesto proposed that Sri Lanka “move away from anthropocentric thinking that places man as the sole owner of the earth which conflicts with nature.”

While international diplomacy efforts have helped signal Sri Lanka’s climate finance ambitions and interest up to now, Sri Lanka’s new president must focus on establishing the institutional mechanisms needed to sustain these efforts. His efforts to combat corruption and “clean up” the government can strengthen the enabling environment to attract new investment. He must also continue – and indeed step up – Sri Lanka’s international engagement on these issues and build on the gains made thus far. These could be critical to meaningfully advance Sri Lanka’s climate finance ambitions.