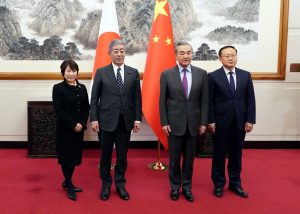

In late December Japanese Foreign Minister Iwaya Takeshi visited China, where he took part in a series of meetings with his counterpart Wang Yi and other Chinese officials. The trip gave the impression that Japan’s relations with China were on the mend. Iwaya indicated that Japan would be open to hosting a Japan-China-South Korea Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in early 2025, and it has been reported that Japanese Prime Minister Ishiba Shigeru himself may travel to China. What lies behind these new developments in bilateral relations, and what might the future hold?

China-Japan relations deteriorated sharply from 2008 to 2012 over the Senkaku Islands issue. Subsequently, attempts being made to turn things around in 2014, and in 2018 then-Prime Minister Abe Shinzo made an official visit to China, suggesting some improvement. Chinese President Xi Jinping was in turn scheduled to visit Japan in April 2020, although the trip was canceled amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Subsequently, relations deteriorated again in light of the growing tensions in China-U.S. relations and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

During his tenure, Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio sought to restore relations with Beijing, hoping to define the shared goals of comprehensively promoting a “mutually beneficial relationship based on common strategic interests” and building “constructive and stable Japan-China relations.” The current Japanese government of Ishiba Shigeru has adopted in full Kishida’s China policy. Ishiba’s words at the Japan-China Summit Meeting held with Xi in Peru, South America, were fundamentally the same as Kishida’s. It still seems that Ishiba has yet to unveil any China policy of his own.

Ishiba’s government is weak, lacking a majority in the House of Representatives. Observers have noted that China has traditionally seemed to prefer dealing with strong governments, of the sort that Abe ran. Things are different now, however, as Beijing appears willing to engage in dialogue with the Ishiba administration. China welcomed the inauguration of Ishiba’s government in Japan, apparently liking the fact that Ishiba had been mentored by former Japanese Prime Minister Tanaka Kakuei, who normalized diplomatic relations between Japan and China, and that he looks up to the former Prime Minister Ishibashi Tanzan, an advocate of “little Japanism.”

For its part, China is seeking to improve relations with the West before the inauguration of the Trump administration, with all of its associated unpredictability. Beijing must view it as a positive that Ishiba does not have particularly strong ties to Taiwan, in contrast to, say, the former Abe faction known as the Seiwa kai. In early December, China sent a large delegation to Japan, including former Finance Minister Liu Wei and many other former ministerial and vice ministerial level delegates. The delegation exchanged views with their Japanese counterparts, after which Iwaya made his visit to China.

Not only is Ishiba carrying on the China policy of the Kishida administration in word, in deed too he seems to be more active than his predecessor in promoting dialogue. One reason for this is a desire to boost relations with Japan’s neighbors before Trump takes office. After all, Ishiba is likely to find it almost impossible to develop the close personal relationship with Trump that Abe did.

Second, in the realm of domestic Japanese politics, the Seiwa kai has since the start of the war in Ukraine moved closer to Taiwan and has more or less adopted a hardline stance on China. But the influence of this conservative force within the ruling Liberal Democratic Party has diminished markedly, and at least within the party there are no longer any strong objections to improved relations with China.

Third, looking at the political calendar, now is the time to work on the bilateral relationship. Once the House of Councillors election – scheduled for the summer of 2025 – approaches, Ishiba will find it hard to reach out to Beijing given that 90 percent of Japanese are critical of China. If public opinion views Ishiba and the LDP as pro-China, they will inevitably be targeted for criticism during the campaign.

As such, the positions of both Japan and China are converging, and this appears to be creating something that at least looks like an improvement in relations. For both Japan and China, however, this is simply a diplomatic balancing; there will be no change in the security rivalry in the East China Sea or elsewhere, and no matter how many ministers and heads of state come and go, the China Coast Guard is unlikely to scale back its activities around the Senkaku Islands. If the goal is to maintain a dialogue with China that assumes a tough, long-term competitive relationship, then this new initiative by the Ishiba administration to frame China-Japan relations in relation to both security and diplomacy should be applauded. But if China is hoping to strengthen its relationship with a prime minister it views as friendly, then the motivations of Japan and China are at odds. Ishiba will have to carefully explain to the Japanese public and to the international community the meaning and necessity of pursuing dialogue with China.