Even as global attention turned to DeepSeek, which put China at the forefront of artificial intelligence (AI), it is evident that China has yet to achieve its own “Sputnik moment” in the space sector. Some Chinese experts suggest that such a breakthrough could come with the Tianwen-3 mission (2028–2031), which aims to return rock samples from Mars, potentially placing China years ahead of the Euro-American Mars Sample Return mission. However, 2031 remains a distant milestone.

Meanwhile, the China-U.S. technological rivalry intensifies, and writing by Chinese experts about space is obsessed with the United States, seeing it as the only benchmark deserving attention. The efforts of Europe, India, and Japan in this area are not even seen as worth mentioning to Chinese analysts. Looking at China’s space sector in early 2025, a clear pattern emerges: a methodical, long-term strategy shaped by military ambitions, aspirations for technological dominance, ubiquitous commercial considerations, and the familiar guiding hand of the state in industrial policy. This is a vision, as top leader Xi Jinping has suggested, of space exploration with “no end.”

Over the past quarter century, China has transformed from a minor player in the global space industry into a major power. Two decades ago, China’s space industry was still describing itself modestly as learning through trial and error. Today, Chinese analysts describe its space prowess with positive terms often applied to other industrial sectors: “big but not strong,” “playing catch-up,” sometimes “running with the pack,” and, in certain areas, “leading the pack.”

The notion of “big but not strong” is drawn from the Made in China 2025 initiative, which included aerospace as one of the 10 strategic sectors. According to that vision, while Chinese companies benefit from market scale and production capacity, they must climb the innovation ladder to achieve global leadership – and the key word here is leadership. This applies not just to space but also to China’s digital infrastructure, commercial ports, and high-tech industries such as advanced materials and new energy vehicles.

China’s space strategy is driven by the state but seeks to draw lessons from private sector innovation. Although Beijing maintains strict financial, regulatory, and institutional oversight, it has encouraged a new wave of commercial space firms that are pushing the boundaries of engineering and market-driven applications. While China’s space sector has not yet reached parity with the United States, its commercial space industry is rapidly evolving in a highly competitive environment, creating the possibility of a national champion emerging within the next decade. These firms view SpaceX and its Starlink network as the benchmark for innovation, emphasizing rapid iteration, cost reduction, and adaptability to market needs.

China’s private space companies are key to understanding its broader ambitions. Unlike their Western counterparts, which often rely on government contracts, Chinese commercial space firms tend to focus on consumer-driven commercialization. They take more risks, embrace more flexible business models, and integrate satellite technology into everyday applications. Companies such as Huawei, Xiaomi, and BYD are incorporating satellite communication into smartphones and electric vehicles, reflecting China’s push to merge space technology with consumer markets. A critical element of China’s strategy is securing access to limited space resources, particularly the satellite frequency spectrum for communication. As companies like SpaceX’s Starlink claim more of the non-geostationary orbit (NGSO) spectrum, Chinese firms are aggressively pursuing their own allocations.

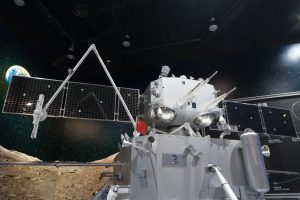

Beyond its economic ambitions, China’s space exploration efforts serve as both a showcase of its technological advancements and a reflection of its broader geopolitical aspirations. Under Xi’s leadership, China has achieved major milestones, including the Chang’e-5 lunar mission, the completion of the Tiangong space station, and the Tianwen missions to Mars. These successes illustrate China’s growing autonomy in space and its determination to rival the United States as a global space leader.

For Beijing, space exploration is deeply tied to national pride and serves as one of many engines for the Communist Party to cultivate its political legitimacy – as is true of any large-scale achievement capable of inspiring collective enthusiasm and pride in Chinese society. The government portrays these successes as part of China’s “great rejuvenation,” reinforcing its image as a technologically advanced power. While a leading Chinese official may describe the space program as “a magnificent poem of mankind from the Earth to the vast universe,” it is also a political statement, showcasing China’s ability to compete at the highest levels of innovation.

However, China’s space ambitions extend beyond prestige – they are, perhaps more importantly, central to its military strategy and evolving views on the nature of warfare and the military balance. In April 2024, China undertook a major reorganization of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), dissolving the Strategic Support Force (SSF), which was established as part of Xi’s military reforms in 2016. As a replacement, three new entities were created under the direct command of the Central Military Commission: the Aerospace Force (ASF), the Cyberspace Force, and the Information Support Force.

The ASF is now one of only two independent space forces worldwide, inheriting the responsibilities of the former SSF’s Space Systems Department (SSD). This reform underscores China’s commitment to enhancing its space warfare capabilities – a modernization effort that began in the 1990s and aims to reduce Chinese military vulnerabilities to U.S. dominance. Space-based assets have long been critical for intelligence, communication, and military operations, and are thus described as “critical infrastructure” within China’s “space security.” China thus views space as both a domain for “first strike” operations in armed conflicts and a theater for hybrid warfare during peacetime.

Alongside its focus on military power, space is also integrated into China’s foreign policy. While competition with the United States remains the center of gravity of the program, “China is willing to work with all nations to explore the mysteries of the universe, promote the peaceful use of outer space, and advance space technology for the benefit of all humanity,” according to Xi. The as-yet-hypothetical International Lunar Research Station (ILRS), which is being developed in partnership with Russia, highlights China’s ambition to lead an alternative global space alliance. While the war in Ukraine has complicated Russia’s involvement, China continues to build partnerships through initiatives such as the Tiangong space station and international satellite programs. So far, Venezuela (providing access to ground stations), South Africa, Azerbaijan, Pakistan, Belarus, Egypt, Thailand, Nicaragua, Serbia, Kazakhstan, and Senegal have joined the ILRS. Argentina, which hosts a Chinese deep-space station in Patagonia, is also a key node in this Chinese international strategy.

Both the facts and writings by Chinese experts, therefore, demonstrate how Beijing’s space program now reflects a broader pattern of its industrial development: methodical, state-guided, and aimed at achieving long-term strategic advantages by eyeing scale and cost reduction. China may not have yet achieved a defining “Sputnik moment,” but it is certainly working hard to create the conditions for a strategic breakthrough.

This article was originally published as the introduction to China Trends 22, the quarterly publication of the Asia Program at Institut Montaigne. Institut Montaigne is a nonprofit, independent think tank based in Paris, France.