An innocuously titled Hindi film, “Mrs,” which starkly depicts the typical Indian housewife’s grueling burden of domestic chores in a patriarchal home, has sparked heated debates on women’s rights and the normalization of patriarchy.

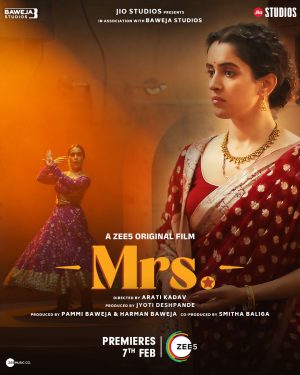

Helmed by popular actor Sanya Malhotra, the film, which is a remake of the 2021 Malayalam film, “The Great Indian Kitchen,” casts an unflinching gaze on the unpaid domestic labor of Indian women.

It is not often that a mainstream Hindi film stays away from the popular song and dance routine and holds up a mirror to society so realistically that it makes the “audience squirm in their seats.” Not surprisingly, the movie has drawn the ire of conservatives and men’s rights groups, who have labeled the film as being a “toxic feminist” portrayal.

“Mrs” portrays a newly-wed woman, Richa (Malhotra), whose hopes of an idyllic married life are soon snuffed out by the demands on her as a dutiful daughter-in-law and wife in a traditional home. Not only is she confined to the drudgery of the kitchen but also, she has to comply with the diktats of the men in the house. Her attempts to continue her career as a dance teacher are openly thwarted by her supposedly loving in-laws.

Men’s rights groups like the “Save Indian Family Foundation” have labeled the film as propaganda of toxic feminists. They have called for a ban on the film. Where is the “oppression” of “a happy young woman cooking food, doing dishes and pressing cloths [sic] of her father-in-law?” they have asked.

The film lays threadbare the rankling misogyny and inherent patriarchy in the so-called “happy Indian family” set-up — an image that has been unquestioningly perpetrated and perpetuated through generations.

To realistically assess the enormity of the issue, it is imperative to examine statistical data. As per the Economic Survey of 2018, Indian women spend 9.8 times more time than men on unpaid work. Significantly, globally, this figure is just three times. This unpaid work includes housework, child-rearing, and care of the elderly.

The gender disparity is also underscored in data from India’s first national Time Use Survey in 2020 conducted by the National Statistical Office. A whopping 81 percent of women are engaged in unpaid domestic services as compared with 26 percent of men. In Indian society’s strictly gendered norms of housework, women and girls are conveniently shackled to the kitchen and domestic chores, leaving them with no economic independence or careers.

Interestingly, the film has resonated with women. Some described young women’s reluctance to marry as “the fear of being reduced to a free cook and maid.” “Mrs” has garnered 1.9 million posts on Instagram with the majority sharing experiences of themselves, their mothers, and relatives.

Incidentally, one of the reasons why the film has struck a chord is because it is not the typical cinematic depiction of gender violence in an impoverished home but the normalized patriarchy in educated middle-class urban homes.

The film conveys the erosion of Richa’s self-identity and her dehumanization, sans melodrama and jarring background scores. For instance, Richa’s father-in-law insists in a rather matter of fact manner that she must prepare chutney (paste) on a grinding stone and not in an electronic mixer since it tastes better.

“Mrs” touches upon concomitant issues of marital rape within the bounds of marriage, which incidentally is not illegal under Indian law.

Richa’s plight — she gets no support from her parents — is similar to what countless other Indian women face. When caught in toxic marriages, most women are advised even by their parents to “adjust” in their matrimonial homes.

The film depicts abuse without showing physical violence. Indian women bear mental and emotional torture with stoic silence, which in turn is glorified as the epitome of Indian womanhood — self-sacrificing and serving others. Any spark of self-assertion or identity on the part of the woman is perceived as selfishness and a betrayal of the family.

While the Hindi remake has succeeded in reaching out to a larger pan-Indian audience, it differs from the Malayalam original in certain respects. “The Great Indian Kitchen” provided stark imagery of the backbreaking work that goes into the practice of daily cooking so effectively that it induced stomach-churning revulsion in the audience. For instance, the woman is shown having to remove from the table the chewed-up remnants of food eaten by her husband and father-in-law. The Hindi remake has a more pleasing aesthetic.

Importantly, in the original film, director Jeo Baby did not shy away from portraying how religion — in this case, Hindu religious rituals — is used to normalize patriarchy. “Mrs” stays clear of that. As the Newslaundry website noted, in “Mrs,” there is a “conspicuous exclusion of how religion and caste intermingle with gender bias within the family,” diluting the nuances presented in the Malayalam original.

This was possibly to ensure that the Hindi film would reach its audiences and not get caught in a Hindutva backlash. Previously, several filmmakers have seen their films hijacked by self-appointed custodians of the Hindu faith. Additionally, films in southern India have far greater freedom in storytelling than in the north where they run into more regressive and Hindutva supremacist mindsets.

But even this watered down version in “Mrs” is unpalatable to India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Its member of parliament and actor Kangana Ranaut ranted on Instagram to defend traditional Indian values and marriage.

Without naming the film, Ranaut lashed out at “Bollywood films for distorting the idea of marriage.” She claimed that as per Indian shastras (scriptures), marriage was “dharma” or “duty” and followed to nurture the young and take care of the elderly. The former beauty queen-turned-Hindutva votary has warned women that if they “try to get too much validation… [by asserting themselves] you will end up alone with your therapist.”

Ranaut also lashed out at critics of the Indian joint family system and women’s role as nurturers, a script that resonates strongly with the Hindu supremacist BJP.

While women like Ranaut are the flagbearers of patriarchy and actively work to disempower women, it was a male director, Jeo Baby, who made a film that exposed the inherent oppression of Indian women in marital domesticity.