Bougainville is often touted as the world’s next newest nation, set to supplant South Sudan with that status. Over five years have passed since Bougainvilleans voted resoundingly to secede from Papua New Guinea (PNG), but progress on realizing this has stalled. The path to independence in this autonomous region, a collection of islands and atolls home to 300,000 people, remains strewn with political roadblocks and practical hurdles.

Bougainville’s president – Ishmael Toroama, a former rebel commander – has championed independence as his principal political project. But he faces an array of challenges. Parliamentary inertia in Port Moresby is obstructing the implementation of the referendum result. And shaping the contours of a future sovereign state is no simple feat; Bougainville must develop the institutional and fiscal capacity to function as a viable, self-reliant nation.

Strong secessionist sentiments have long flourished in Bougainville. They are rooted in the region’s distinct sociocultural identity as well as historical grievances over resource exploitation and political marginalization.

Bougainville first proclaimed independence in 1975, two weeks before PNG gained its own sovereignty from Australia. But this unilateral declaration failed, and so the region was reluctantly absorbed into its larger Melanesian neighbor, which lies across the Solomon Sea.

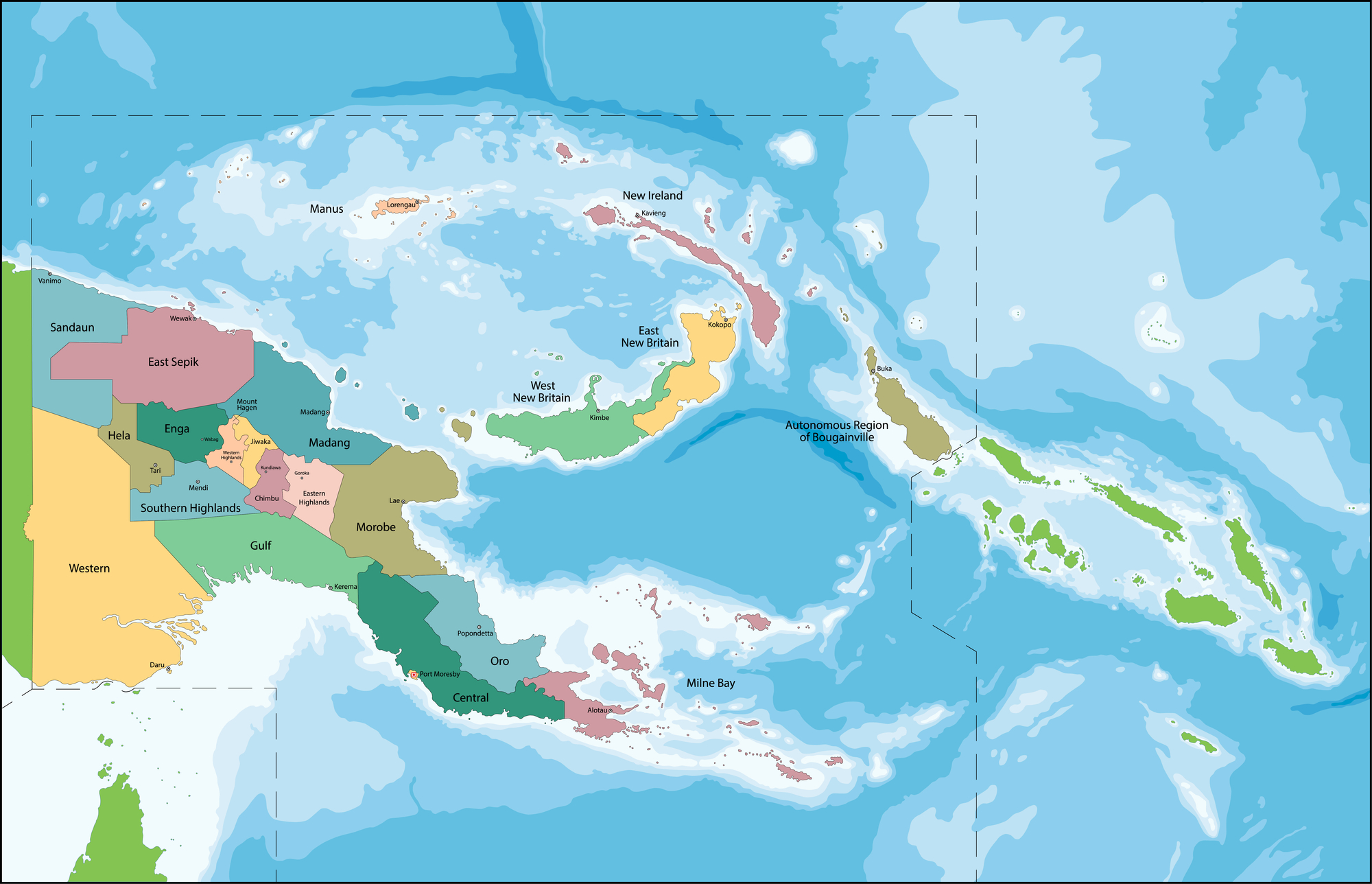

A map of Papua New Guinea, with the Autonomous Region of Bougainville visible in the country’s far east. To the east of Bougainville is the Solomon Islands.

Tensions continued to simmer over the following decade. They erupted into outright conflict in 1988; the environmental impacts and inequitable economic exploitation of the Panguna copper mine in Bougainville fueled an intensifying nationalistic fervor. A brutal nine-year civil war with Port Moresby ensued. It claimed the lives of 20,000 Bougainvilleans, displaced 70,000 more, and left the region’s economic and social infrastructure in ruins.

A peace agreement was brokered in 2001. It led to the creation of the Autonomous Bougainville Government (ABG) and featured a commitment to a non-binding referendum on independence, which was held in 2019. In the referendum, 97.7 percent of voters cast their ballots in favor of secession; 1.6 percent opted instead for greater autonomy from PNG.

This vote marked an unambiguous manifestation of the people of Bougainville’s will. And yet the future of the region remains uncertain. As the referendum is not legally binding, it must first be ratified in the PNG Parliament before Bougainville’s sovereignty can be secured, but efforts at ratification have been slow and contentious.

Progress was made when Port Moresby and the ABG signed the Era Kone covenant in April 2022. It contained two critical dates: the referendum result must be tabled in Parliament by 2023. and the two governments must then determine a political settlement for Bougainville no later than 2027.

The first deadline has long since passed, however, without any indication that the result will soon be placed on the parliamentary agenda. Although Port Moresby has reaffirmed its commitment to the covenant on several occasions, recognition of the result continues to face delays. As 2027 edges closer, meeting the second deadline to determine Bougainville’s political future appears increasingly doubtful, too.

There are several reasons for these delays, including a key dispute over parliamentary procedure. The ABG has contended that a simple majority would suffice to ratify the result. PNG has insisted instead that a two-thirds majority – mandated for constitutional amendments – is required. The government argues further that it remains Parliament’s prerogative to determine its own appropriate voting threshold.

A two-thirds majority means at least 79 of PNG’s 118 parliamentarians must endorse the result. It is not certain that they would unite in such force behind a move that may challenge Port Moresby’s authority and subvert its interests.

There is some reluctance to establish a precedent for secession that could embolden provinces harboring separatist sentiments, like East New Britain, New Ireland, and Enga. An independent Bougainville would also deprive PNG of the region’s rich resources, including minerals, cocoa, and copra.

And so Bougainville’s independence is not a foregone conclusion. Indeed, PNG has emphasized that under the 2001 peace agreement the final decision to ratify the result rests with Parliament. Lawmakers, the government asserts, possess the authority to determine an alternative political settlement.

The resounding clarity of the referendum, however, indicates that this region will not accept anything less than the realization of its secessionist aspirations. Bougainville published a draft of its proposed constitution last year. The ABG could invoke it to bypass Parliament and legitimize another unilateral declaration of independence. This would mark a bold assertion of sovereignty, although it does not guarantee recognition from the international community.

Last year, PNG and the ABG appointed Sir Jerry Mateparae, a former New Zealand governor-general, as a mediator to revive talks on Bougainville’s political future. This may help resolve the impasse that has stalled negotiations.

But there are further obstacles to independence. Bougainville lacks at present the institutional capacity and fiscal means to confront the practicalities of modern statehood. Despite its plentiful mineral resources, Bougainville’s economy is small and undiversified. The region is reliant on central government subsidies and agriculture.

Bougainville’s internal revenue – largely dependent on income tax from ABG public servants paid from the national purse – amounts to just 7 percent of its total budget. A recent research report concluded that an independent Bougainville would require a budget two or three times greater than its current one. This fiscal gap cannot be readily remedied.

James Marape, the prime minister of PNG, has insisted his government must navigate the post-referendum process “responsibly and compassionately.” But he declared in December that Bougainville has yet to achieve the economic self-sufficiency required to survive as a sovereign state.

Many of the foundational institutions of a future independent Bougainville – a legal system and taxation authority among them – are also inchoate. And certain public services central to a functioning nation-state are chronically underfunded and ill-equipped to address the scale of the region’s development challenges.

This includes healthcare and education. Only one functioning hospital and a handful of health centers serve Bougainville’s 300,000-strong population. At the same time, infant mortality and preventable disease rates are alarmingly high. Just 10 percent of the region’s residents have reliable access to electricity. And there is a dearth of employment prospects for youth in a region where the median age is 20.

The ABG is taking steps to address these challenges, bolster its institutional capacity, and extend its autonomy. The Sharp Agreement – signed by the two governments in 2021 – is accelerating the transfer of powers from Port Moresby to Bougainville. 59 powers can be drawn down from the central government, empowering the ABG to manage its internal affairs. Last year, the region opened a law and justice center, instated a chief tax collector, and established the Bougainville Energy Office.

The ABG also published an economic roadmap to strengthen its fiscal self-reliance. Although mining has a fraught history in Bougainville, it may emerge as the foundation for independence. Around $60 billion in mineral reserves – mostly gold and copper – remain in the region.

There are plans to reopen the infamous Panguna mine, which was at the epicenter of the conflict that ravaged the region in the late 20th century. Back then, the mine’s profits largely flowed to investors in Port Moresby and abroad, and its operations inflicted devastating environmental damage. Close to a billion tonnes of mine waste was released into local rivers, contaminating water sources and disrupting vulnerable ecosystems.

The ABG has now renewed the exploration license of Bougainville Copper Limited, which will soon be majority-owned by the government. The company has also signed a Land Access Compensation Agreement with landowners. Local officials have welcomed these developments, as Panguna’s projected revenue is $36 billion over 20 years.

Toroama has also sought greater international investment in the region. The ABG is exploring ventures with Chinese state companies, including the China Railway 25th Bureau Group, for major development projects.

But it is the United States in particular that Toroama seeks to court. He visited Washington in November 2023 and appears intent on securing U.S. support for the region’s independence and economic development. There is even some suggestion that Toroama is willing to welcome a permanent U.S. military base at Cape Torokina, which hosted a U.S. airfield during World War II.

Indeed, it is impossible to abstract Bougainville from the broader rivalries that are roiling the region. As Beijing and Washington tussle for power in the Pacific, Bougainville’s strategic location and resource wealth ensure it will not escape external interest. Its aspirations for sovereignty may only become further entangled in the machinations of regional actors.

Uncertainty looms ahead of the presidential and parliamentary elections in October this year. Although Toroama is running again, there is no guarantee that he will not be replaced by a rival who may tether the region to Beijing.

In the end, nation-building is no simple endeavor. Bougainville faces an array of challenges – political, practical, and developmental hurdles among them – that obstruct its long-awaited welcome to the world stage. But there is an air of inevitability building among Bougainvilleans, grounded in the legitimacy of the resounding referendum result.

As Bougainville continues its struggle for independence, a nation in waiting holds its breath.