Facing 2.4 million cyberattacks a day, Taiwan’s cyber resilience is relentlessly tested by an onslaught of increased and sophisticated cyber threats. Government agencies, critical infrastructure, and private industry are all in the crossfire, turning cybersecurity into a fundamental national security issue. These threats are part of a broader strategy of cyber warfare, targeting Taiwan’s institutions, disrupting essential services, and probing for vulnerabilities in its national defenses.

This challenge is only intensifying. Cyber threats surged in 2024, reflecting a rapidly expanding attack surface. As adversaries deploy artificial intelligence (AI) enhanced techniques, espionage campaigns, and data breaches to critical infrastructure, Taiwan’s cybersecurity posture is insufficiently implemented, enforced, and funded.

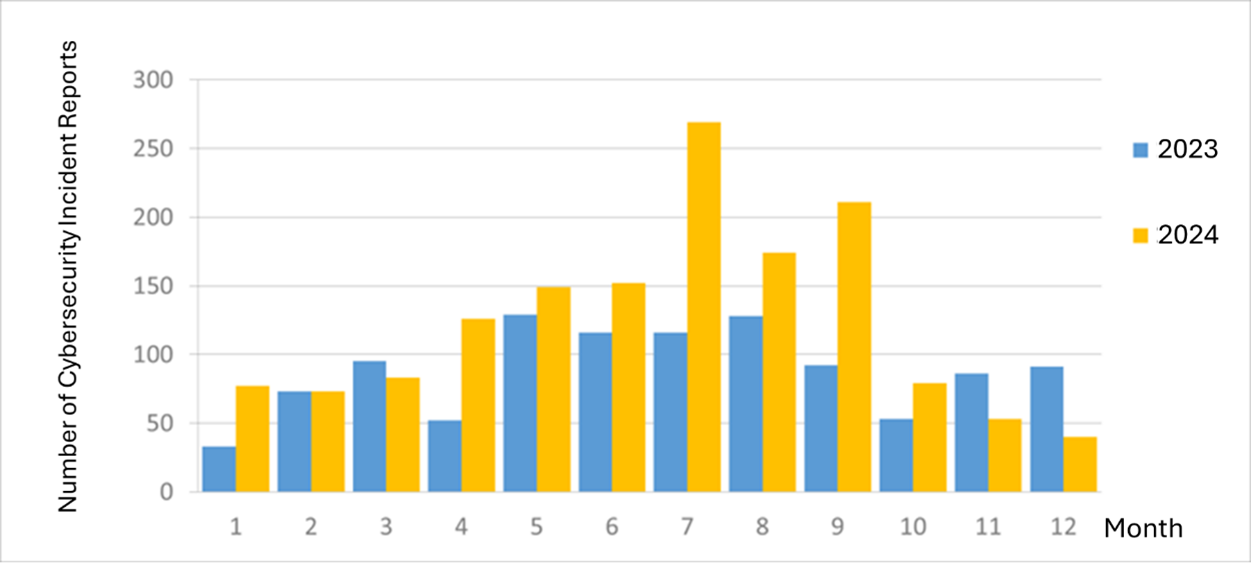

The number of monthly cybersecurity incident reports in Taiwan in 2023 vs 2024. Source: Taiwan’s Administration of Cyber Security, December 2024 Cybersecurity Report.

Despite the escalating risk, the government is now facing budget constraints that threaten to undermine cybersecurity readiness at a time when investment in cyber defense is needed most.

In January, the Legislative Yuan approved a 6.6 percent reduction in government spending, which threatens to slow security initiatives – such as critical infrastructure projects, workforce development, and AI research – at a time when China is expanding its AI-focused cyber warfare capabilities. In real terms, this could hinder government agencies’ cybersecurity spending. For example, the National Security Bureau’s 2025 fiscal year budget originally aimed to invest roughly $500,000 for the construction of a cybersecurity operating platform environment and over $1.5 million for a network transmission integration operating center.

In response to the legislature’s decision, Taiwan’s president, Lai Ching-te, has pledged to increase defense spending to over 3 percent of GDP, but it remains unclear how much will be allocated to cyber defenses, which are often excluded from traditional conceptions of the defense budget.

This budget cut could not have come at a worse time. Last month, Taiwan’s Administration for Cyber Security, under the Ministry of Digital Affairs (MODA), released a damning report highlighting the serious lack of cybersecurity controls across nearly all government agencies. It cited that 47.5 percent of recorded incidents were due mainly to human error by personnel unknowingly downloading malware onto agency networks by clicking on malicious links and connecting to unsafe applications and other equipment.

Around the same time, in an interview with the American Chamber of Commerce in Taiwan, Lin Ying-dar, president of the National Institute of Cyber Security and (NICS), expressed some of the key challenges impacting Taiwan’s cyber defense readiness.

Chief among them is the concern over the rise of offensive AI, which Lin explained as the next stage in the evolution of cyber threats. Malware traditionally follows a preset path; by incorporating AI it can now become more intelligently dynamic, shifting to adapt to its environment in an information system to better target its victim. To counter this emerging threat, Lin said, blue teams (defensive security) must also harness AI to deter these types of attacks, with the challenge not only being a deep understanding of the tool but integrating it fully and effectively into the environment.

And the pressure is on. In recent years, China state-backed advanced persistent threat (APT) groups, such as APT41 and Mustang Panda, have been developing AI-enhanced cyber weapons to target Taiwan’s government agencies, financial systems, and critical infrastructure.

Taiwan has also experienced an escalation of AI-generated disinformation campaigns coming from China. With 2.159 million instances of disinformation last year alone, AI bots deploy and spread fake news and propaganda across social media, online forums, Chinese media outlets, and other mediums. Another alarming development is China’s use of deepfake technology to fabricate video clips of Taiwanese political figures’ speeches, attempting to mislead the public’s perception and understanding.

To meet these challenges, Taiwan will need to focus its efforts more on the second and third strategic pillars of its National Cyber Security Program (NCSP), which aim to “promote public-private partnership and collaborative governance” and to “make good use of smart and forward-looking technology for proactive defense against potential threats.” It can do so by increasing its partnerships with leading Taiwan-based AI-cybersecurity companies, like CyCraft Technologies, to adopt and scale advanced strategies and tools for defense.

While AI-powered cyber threats pose a growing challenge across all sectors, Taiwan’s critical infrastructure remains particularly vulnerable, leaving power grids, transportation networks, and undersea cables at risk. In his interview, Lin highlighted the gap between Taiwan’s information technology (IT) and operational technology (OT) security, explaining that most cybersecurity investment has focused on IT over OT. This is alarming because OT critical infrastructure is a prime target for cyberattacks. With the goal of disruption, data theft, espionage, and financial gain, attackers focus on industrial control systems that operate power stations, pipelines, transportation services, high-tech manufacturing facilities, and the most targeted, telecommunications.

As reported in the National Security Bureau’s “Analysis on China’s Cyberattack Techniques in 2024,” attacks against the telecommunications sector grew 650 percent since 2023, making it a key area of China’s chosen targets for cyberattacks. This industry-wide threat bore true in early 2024 when Taiwan’s largest telecommunications company, Chunghwa Telecom, fell victim to a massive data breach. Alleged Chinese hackers successfully infiltrated the company’s systems and stole approximately 1.7 terabytes of data, which included military documents and government contracts and were subsequently posted for sale on dark web marketplaces.

Even with clear threats to Taiwan’s critical infrastructure, its slow adoption of Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA) has left key systems exposed, raising concerns about the effectiveness of its overall security strategy. Under section 3.2 of the third strategic pillar of its National Cyber Security Program (2021-2024), the only directive action is to “evaluate and introduce the Zero Trust Network and gradually try to verify its feasibility.” While there has been a general push by the national government to enhance ZTA, focusing on user identity, device identity, and trust evaluation, implementation remains in the early stages, as Lin described. Many government agencies still operating on legacy systems, making ZTA integration complex.

However, there have been bright spots. New Taipei City was recognized for its “Zero Trust Cybersecurity Collaborative Defense System” in 2023 by the IDC and again in 2024 by The Open Group, showing promise for future adoption by municipal and national government system architecture and security.

Beyond its technical and policy challenges, Taiwan also faces a fundamental issue: a severe shortage of skilled cybersecurity professionals. Internally, the Administration for Cyber Security’s 2025 budget report emphasized this stark disparity, stating the number of roles required for government cybersecurity operations is 165, but the actual number employed is only 81, meaning the agency’s workforce is operating at less than 50 percent capacity. Zooming out, the report also notes that while the cybersecurity staffing occupancy rate is 90.3 percent across all government agencies, showing an improvement in hiring, there is a lack in specialized areas such as policy and compliance, cyber threat intelligence, incident response, auditing, and risk assessment.

Why are there so many vacancies? Unfortunately, this shortage is a global trend. The World Economic Forum stated that there are 4 million more cybersecurity job openings than there are qualified candidates. For Taiwan, there is also strong competition with the United States, Japan, and the private sector, making public-private partnerships all the more essential.

Additionally, Taiwan lacks a fully conceived cybersecurity workforce development plan. This gap contrasts with Japan’s Cybersecurity Human Resource Development Plan, South Korea’s Cybersecurity Master Plan, and Singapore’s Cyber Security Agency Talent Development Initiative, which provide structured pathways for training and workforce expansion. However, the Administration for Cyber Security’s 2025 budget report does outline proposed solutions for such a plan, including vocational programs, university partnerships, scholarships, job transition training, and more. It also has a blueprint for cybersecurity education and training on its website.

With all these challenges in mind – funding, AI, critical infrastructure, Zero Trust, workforce shortage – the focus must now shift to how Taiwan can strengthen its overall cybersecurity posture to meet the growing threats ahead.

First, an assessment of Taiwan’s national cybersecurity objectives reveals that their implementation has fallen short of expectations. Modifications to the Cyber Security Management Act need to be made to ensure effective execution. This includes stronger enforcement practices for mandated cybersecurity standards. Due to weak enforcement mechanisms, many government agencies and private firms fail to meet compliance requirements and remain unaccountable. To improve its position, Taiwan could strengthen its penalty system by increasing fines for general non-compliance, which is significantly low compared to international standards (up to $31,600 in Taiwan, compared to $660,000 in Japan, $749,000 in Singapore, $21.5 million or 4 percent of revenue in the EU, and tens of millions in the United States).

Next, for Taiwan’s Phase Seven (2025-2029) of its National Cyber Security Program (NCSP), which has yet to be published, priorities on technology and security framework implementation should be made clearer and more actionable. Simply stating that Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA) will be introduced to “gradually try to verify its feasibility” is not measurable and lacks agency. While the Administration for Cyber Security provides information on security audits in general, the existing NCSP fails to include whether an assessment or audit would be performed to make this evaluation for ZTA. To see greater results, there needs to be a better definition of the success criteria.

This is especially important for Taiwan’s AI security ambitions. Despite AI’s recent global introduction as an accessible and scalable technology, the NCSP only mentions it in one line of its development vision, saying, “we aim to accelerate the integration of AI.” Looking ahead, it is imperative for Taiwan to develop an AI cybersecurity framework to set guidelines for AI-based security solutions and mandate security audits for AI-based products. This could be accomplished by aligning to the already existing EU AI Act and NIST AI Risk Management Framework. Additionally, AI-powered tools for defensive security should be further adopted to counter the technology’s offensive use cases.

Lastly, Taiwan can formalize regional and private sector partnerships through its National Information Sharing and Analysis Centers (N-ISAC) to strengthen collective cyber resilience. In 2019, Taiwan and Japan entered into an agreement through the Financial Information Sharing and Analysis Center (F-ISAC) to exchange intelligence on financially linked cyberattacks. Similarly, regional collaboration through the N-ISAC could provide Taiwan and its allies with deeper insights into new and emerging threats, particularly those coming from China.

To bridge these critical gaps, Taiwan’s cybersecurity future depends on decisive action and a commitment to strengthening its digital defenses. If the government continues down its current path – underfunded, under-enforced, and falling behind in areas like AI security and Zero Trust implementation – then the consequences will extend far beyond network disruptions. A large-scale cyberattack could cripple critical infrastructure, compromise national security, and erode public trust in the government’s ability to protect its institutions.

Taiwan does not have the luxury of time. The threats are evolving, and so must its response. The question is no longer if Taiwan will be targeted, but whether it will be ready when the next attack hits.