NEW YORK — In a packed hall overlooking the United Nations Headquarters, Kazakh nuclear justice advocate Aigerim Seitenova premiered her documentary “JARA — Radioactive Patriarchy: Women of Qazaqstan.” The screening took place on the sidelines of the Third Meeting of States Parties of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW).

The independently produced documentary unearths the environmental destruction and humanitarian effects caused by the 456 nuclear tests conducted in Kazakhstan over the course of 40 years by the the Soviet Union.

Seitenova, a third-generation survivor of Soviet nuclear testing, was motivated to confront and understand her own family’s nuclear legacy. She is also a co-founder of the Qazaq Nuclear Frontline Coalition, which aims to empower nuclear affected communities by strengthening their role in civil society.

The film weaves together six testimonies from women in nuclear-affected regions, focusing on the gendered impacts of radiation, the consequences of technocratic militarization, and the leadership of women within local communities.

In Kazakh, “Jara” means “wound” and the viewer is reminded of how, for so long, the these voices were never heard.

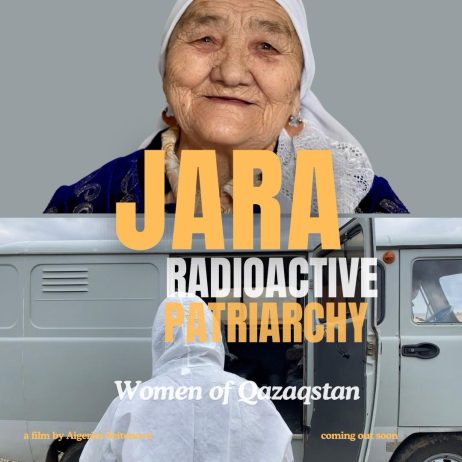

Poster for Aigerim Seitenova’s film.

“This film is a labor of love and me sharing my vulnerability with the world,” Seitenova said in a speech introducing the film. “I wanted to uplift my agency and theirs, to share our stories as legitimate without us only as victims but agents of change and owners of our stories.”

The film is dedicated to Seitenova’s grandmother, who lost three out of her 12 children and her husband to the consequences of nuclear testing. By the time Seitenova was born, her grandmother had lost her sight.

“All she could see was a shadow of my silhouette… I wished she could have seen me, but I am happy she heard my voice loud and clear. Now I use that same voice to advocate for nuclear justice. She would have loved that,” Seitenova said.

Seitenova plans to screen her film in major European cities, such as Berlin, Paris, and London, in the coming months. She will present her film at Harvard University’s Davis Center on March 13.

The event was part of a series of side events to the Third Meeting of States Parties of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW).

Kazakhstan was among the original 50 states that signed and ratified the treaty prohibiting nuclear weapons in 2018. Kazakhstan’s First Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Akan Rakhmetullin led the conference this week.

President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev has called for the “complete renunciation of nuclear weapons by 2045.” Kazakhstan is the only Central Asian country party to the TPNW.

The legacy of nuclear weapons testing remains in the historical memory of Kazakhstan. At the Semipalatinsk Test Site, the Soviet Union conducted 116 atmospheric nuclear weapons tests and 340 underground nuclear tests. The last nuclear test was conducted at the site in 1989.

Despite the closure of the site in 1991, the effects of Soviet nuclear testing still lingers. Civilians living near the test site were exposed to high levels of radiation leading to increased cases of cancer and genetic disorders.

Diana Serikzhankyzy, born and raised in Semey, formerly Semipalatinsk, was diagnosed with dysarthria, which prevented her from developing the ability to speak.

Before a crowd of youth leaders attending the conference, Serikzhankyzy shared her testimony and her struggle to overcome the long-lasting effects of nuclear testing.

“I have lived among children without eyes, without the ability to hear or speak. They dream of having what so many politicians take for granted,” Serikzhankyzy said.

Diana Serikzhankyzy stands beside the famous “knotted gun” sculpture, title “Non-Violence,” which stands outside the U.N. Headquarters in New York City. Photo provided by Diana Serikzhankyzy.

The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), which entered into force in 1970, recognizes China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States as “nuclear weapon states” in exchange for their gradual disarmament and support of non-nuclear weapon states’ access to peaceful uses of nuclear technology. By contrast, the TPNW directly calls for the complete abolition of nuclear weapons.

Yerdaulet Rakhmatulla speaks at an event on the sidelines of the Third Meeting of States Parties of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). Photo provided by Yerdaulet Rakhmatulla.

Yerdaulet Rakhmatulla, who co-founded the Qazaq Nuclear Frontline Coalition, said, “thanks to Kazakhstan’s leadership of the conference we now have greater visibility.”

The coalition engaged in various side events at the conference, most notably at the “Nevada-Semey 2.0” meeting, which focused on revitalizing cooperation between the United States, First Nations, and Kazakh communities.

“Nuclear justice is one of the few areas where our government has worked closely and effectively with civil society. This has been a progressive step in the right direction” Rakhmatulla said.

The nuclear abolitionist conference at the United Nations this week saw various members of civil society, from faith leaders to activists, take part alongside policymakers.

As the northeastern winds washed through the streets of New York, the flags of 193 nations fluttered before a lonesome tower symbolizing the hope of humanity now 80 years old. The memory of Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the Cold War’s nuclear anxieties may be fading in some places, but not among those who directly bore the cost.

“I will fight for a world free of nuclear weapons,” pledged Serikzhankyzy. “My country and I have paid too high a price.”