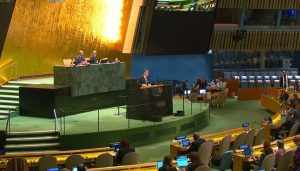

On March 4, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution to established a U.N. Regional Center for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Almaty, Kazakhstan, with the support of 152 countries.

Kazakhstan’s presidential administration, Aqorda, called the adoption a “significant foreign policy success for Kazakhstan.”

Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev first proposed a regional SDG center in September 2019, during his address to the U.N. General Assembly’s 74th General Debate. At the time, he noted the opening, in May 2019, of a new “Building of International Organizations” in Almaty, which already hosted 16 U.N. agencies. “As the next step, we propose to establish in its premises a U.N. Center for SDGs with [the] mandate to assist countries of Central Asia and Afghanistan,” he said.

Tokayev repeated his desire for such a center at the 77th General Debate in 2022, characterizing it as an important step in furthering regional cooperation amid global turmoil. “We intend to work together with all stakeholders to address a pressing regional agenda that includes climate change, the Aral Sea, rational use of water resources, border delimitation, combating extremism, and expanding intra-regional trade,” Tokayev said in 2022.

The four-page draft resolution, dated February 26, 2025, starts with a lengthy (and traditional for U.N. resolutions) section essentially recounting the history of the Sustainable Development Goals, from their origins in a 2015 resolution packaged as part of the 2030 Development Agenda to various other resolutions touching on international and regional cooperation.

Mentioning “the progress achieved in the Central Asian countries, their integration with economies of Europe and Asia and their contribution to global economic growth,” “shared interests in the further development of regional cooperation among the Central Asian countries for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals and advancing good-neighborly relations,” and touching specifically on the role of regional cooperation in promoting lasting peace in Afghanistan, the resolution calls for the establishment of a U.N. Regional Center for Sustainable Development Goals for Central Asia and Afghanistan. It requests that the U.N. secretary-general appoint a head for the center and outlines the cooperative work envisioned, to be supported by voluntary contributions from U.N. member countries and private sector actors.

In announcing the “unanimous” adoption of the resolution, Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs reiterated Tokayev’s backing of the idea: “President Tokayev stressed that Kazakhstan, as the largest economy in the region, is interested in strengthening cooperation between states and the sustainable development of Central Asia, playing a key role in promoting regional integration.”

152 U.N. member states co-sponsored the resolution. (There are 193 member states in total.)

Kazakhstan’s push for the center serves to reemphasize the country’s commitment to the U.N. system and its role as a central player in connecting the region to the world. It also further highlights the trend toward greater regional cooperation within Central Asia, including Afghanistan and not necessarily centered on China and Russia. This trend can be observed in the steady beat of regional leader meetings, which began in 2018 and by 2022 had hit its stride.

“The adoption of this resolution underscores global support for a regional approach to sustainable development and demonstrates the readiness of the international community to facilitate the progress of Central Asia and Afghanistan on the path to stability, prosperity, and integration into global development processes,” Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs said in a statement following the adoption.

This effort comes at a time when the United States is undergoing what can only be called a convulsive reorientation of its geopolitical outlook. For a taste, it’s worth noting remarks delivered by Edward Heartney, minister counselor for economic and social affairs at the U.S. Mission to the U.N., in regard to Kazakhstan’s resolution. After recognizing Kazakhstan’s efforts to reach consensus, and noting that the U.S. had joined that consensus, Heartney cast cold water on the effort:

… the United States remains skeptical of the need for this SDG Center and, in principle, opposed to expansion of the U.N. system, especially where the likelihood of duplication of efforts and overlapping mandates is high. Kazakhstan needs neither an expanded U.N. system nor the SDGs in order to prosper; it should, instead, make sovereign decisions for its people and cast aside the burden of soft global governance.

Heartney took issue with the “inclusion and constant repetition of references to prior resolutions,” calling it an inefficient practice, and also objected to mentioning non-U.N. organizations. He quibbled with the language used to describe development, stating that “the United States believes it is time to start talking about ‘responsible’ and ‘long-term’ development that aims to move countries up and out of ‘developing’ status. The term ‘sustainable’ fails to indicate the direction and movement we all expect to see.”

Finally, Heartney called the listing of specific categories of people whose human rights should be protected “redundant and unnecessary,” claiming, “Concerning human rights, it is the long-standing U.S. position that all human beings have the same internationally recognized human rights and there are no gradations of human rights.” In these remarks, we see the bleed-over of U.S. President Donald Trump’s crusade against “DEI” – that is “diversity, equity, and inclusion” – from the domestic realm into the international.

The only “human rights” referenced in the draft resolution were those of “all Afghans,” with the “meaningful participation” of women, children, and minorities specified as important.