The Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) has approved a radical administrative restructure that will cut the number of Vietnamese provinces by nearly half, and eliminate an entire level of administration.

Under the changes, which the CPV Central Committee approved on Saturday after a three-day meeting, Vietnam’s administrative system, which currently includes three levels of subdivision – provinces, districts, and communes – will move to a two-level system.

The district level will be eliminated entirely, while the country’s 63 provinces and cities will be merged into 28 provinces and six centrally-run cities. (A full list of the new provinces is available here.) Meanwhile, the number of commune-level administrative units will be reduced by 60-70 percent nationwide.

The CPV’s party committees, which mirror the administrative state, will also be merged and eliminated in line with the above changes, while a host of other CPV-adjacent institutions, such as Vietnam Fatherland Front committees, socio-political organizations, and mass associations, will also be merged and streamlined, VnExpress reported.

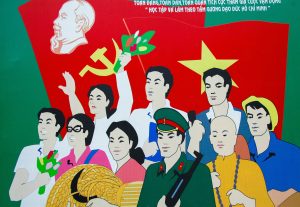

The restructuring is just one part of an ambitious bureaucratic “revolution” that CPV General Secretary To Lam has undertaken since his appointment last year, aimed at cutting waste, tackling corruption, and creating economic development that can drive the country into what state propaganda has described as a new “era of national rise.” Lam has previously called for administrative reforms that will make the party-state “lean, compact, strong, efficient, effective, and impactful.”

Addressing the Central Committee on Saturday, Lam told the delegates that the restructure was “a strategic decision without precedent, aimed at ensuring fast, stable, and sustainable national development, and at better serving the lives of the people,” according to a report by Vietnamnet.

The report added that this round of administrative restructuring is “rooted in scientific, bold, and innovative principles, grounded in current realities and forward-looking – projected to meet the country’s needs for at least the next 100 years.” The elimination of district-level administrative units will require the National Assembly to revise the 2013 Constitution and the 2025 Law on Local Government Organization; otherwise, the changes will come into effect once approved by the National Assembly.

Saturday’s Central Committee decision comes two months after the National Assembly approved a sweeping administrative shake-up that saw the number of ministries cut from 18 to 14, the number of government-affiliated agencies reduced from eight to five, and a similar pruning of CPV commissions and National Assembly committees. The state media, civil service, police, and military also face cuts, and the Vietnamese government says that up to 100,000 people are in line to be cashiered or offered early retirement.

In December, Lam connected this to the anti-corruption campaign that was launched with great vigor by his predecessor, Nguyen Phu Trong, which he helped execute as minister of public security. State agencies should not be “safe havens for weak officials,” he said, according to the AFP news agency. “If we want to have a healthy body, sometimes we must take bitter medicine and endure pain to remove tumors.”

The most important of these changes is the slashing in the number of provinces and independently-administered cities. In a thread on X, Nguyen Phuong Linh argued that this will have several impacts beyond streamlining and cost-cutting. One of these stems from the horizontal division of the Central Highlands provinces and their merger with provinces on the south central coast. Linh argued that this will help remove the Central Highlands as an “independent geopolitical region,” one that, by virtue of its large ethnic minority population, has long resisted central control. The impact, which has also been noted by other observers, is that the number of provincial representatives to the Central Committee will now decrease sharply, “leading to greater concentration of power in the national government.”

Taken together, these reforms represent the most significant since the doi moi economic reforms of 1986, Vietnam’s analogue to China’s “reform and opening,” which placed the country on its current path toward export-led industrialization and relative prosperity. As Duong Thi Thuy Pham and Mai Truong noted in these pages back in January, such a significant restructuring is likely to encounter many challenges, from the tens of thousands of civil servants who are made redundant to the possibility of service interruptions and even new forms of internal factionalism within the CPV.

However, given the recent turbidity of the global economy, Vietnam’s administrative “revolution,” if it is successful, could end up being seen as a prescient undertaking.